is a blog by Brendan

Girlfight (2000): Beating out Gimme The Loot (2012) for the title of “oldest cheap indie movie about hard-luck kids of color in the outer boroughs getting into scrapes, anchored by a charismatic young woman lead, which I have been vaguely meaning to watch since seeing something about it a long time ago,” I’m pretty sure I saw the trailer for this before watching The Way of the Gun (2000) with Jon and Ken in college. And then in 2019 I biked around the corner and rented it! Hail and farewell, Movie Madness!

I don’t know if I’d exactly recommend it but I really enjoyed it, because of who I am as a person, and because this is a movie someone really wanted to make with care and effort. It doesn’t escape the borders of the novice-boxer story template—it even has a love interest named Adrian—nor does it do justice to its side thread about family, domestic abuse and grief. And there’s a queerness that’s trying really hard to squeeze in around the edges of the whole thing, which the movie should have opened up to, and didn’t.

But man, Michelle Rodriguez is one of the most magnetic screen performers on Earth, and gambling on her really paid off here. It was not only her first starring role, it was her first acting job ever! She’s perfect for it. There are some great character actors in here too; I immediately recognized Paul Calderón, who plays her dad, from his scene theft in Out of Sight (1998).

The Ice Storm (1998): I act like I’m a big Ang Lee fan, but the numbers say that I’ve seen two of his movies (Eat Drink Man Woman [1994] and The Incredible Hulk [2008]) once each and one of them (Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon [2000]) like forty times. Having now finally watched this, his most heavily cast-stacked movie and among the most heavily so stacked movies ever, I think I can say: I still like Ang Lee, though I have little interest in his newer work. I still like Kevin Kline, too, who’s not exactly the lead but does really get to put his particular gift to use: he can convey masculine hollowness and fragility with unusual dimension, and with what seems like personal humility.

Watching this beautifully made film made me a little depressed, because it uses its distance from a particular time and age cohort to be excoriating about the failures its subjects were too arrogant or afraid to anticipate. “Wow, what a huge failure that I did not see coming” is a consistent theme of my own reflective writing, so you can see how I might project a bit there. Anyway most of the clothes were accurately awful but I’d still wear everything Tobey Maguire does.

The Driver (1978): Watched while packing, which I think was a good choice. This is a movie where a man drives and is cool, and another man is mad about it. You can feel free to look at the boxes you’re packing during the driving/mad parts. I picked it up because I’d heard it referenced as an influence on Drive (2010), which I still love; I can see the connection now, but its plot was quite different, and actually a bit closer to that of Baby Driver (2017). With regard to that, I’m not sure if this is a deliberate Easter egg or not: in this movie, the protagonist (credited The Driver) and another character named The Kid are enemies. But in Drive, the protagonist goes by both those names.

The World’s End (2013): Speaking of Baby Driver, I watched this while packing too. It was the only Edgar Wright movie I hadn’t seen. There’s some meat here in terms of an attempt to thematically unify the three Cornetto movies, and a potential rabbit hole to go down about the influence they bear from the Hitchhiker’s Guide trilogy: the latter arose from an idea Douglas Adams had about finding a new way to destroy the world on the radio every week, and each Cornetto movie is about British culture in confrontation with the destruction of a way of life. But back at the beginning of that sentence when I said “meat,” I backspaced over “interesting stuff,” because I myself don’t find it that interesting and I couldn’t relate to this movie very much. It’s a nadir for Wright’s narrative space for women and I really don’t care about aggressive masculine drinking as an activity. I did at least enjoy being able to trace Wright’s technical advancement across the movies, because he really is getting more deft with each film. But oh boy, does the climax play differently after a certain 2016 referendum than it did before.

Avengers: Endgame (2019): I don’t have anything new to say here, I’m just glancing at an emergent theme among “put this on while packing” movies and then looking at myself a bit askance.

My Big Fat Greek Wedding (2002): Watched with Kat, AFTER a round of packing. I’d never seen it before, as it came out after I’d given up on romantic comedies, and it was very sweet. It reminded me a lot of While You Were Sleeping (1995), the pinnacle of the genre, and not just in its Chicago setting! This is kind of about what that movie would have seemed like from the perspective of Bill Pullman’s character, in terms of the weight a large family brings to a budding relationship. In fact, this one plays a structural game with the genre: there’s no real will-they-won’t-they between the protagonist and the romantic interest, because all the plot tension is about whether she and her family will compromise for each other in the end.

Anyway I liked it very much, but man, the editing of this movie is the goofiest part. It seemed at times like someone had just installed their first copy of Final Cut and wanted to try out every cut-transition effect in alphabetical order.

Grandmother’s Gold (2018): The first movie I watched as a resident of Chicago! Last year Kat introduced me to the extraordinary web series The Gay and Wondrous Life of Caleb Gallo, a delirious expression of pure auteur vision that an old tumblr friend described as “millennial opera.” That rings completely true while also underselling how weird and funny it is. Its creator, Brian Jordan Alvarez, has made many other videos, including a couple of negative-budget features like this one.

The best part of the movie is that it’s mundane sci-fi about technological regression, which then sideslips into cosmological fantasy, all done in a blithe and goofy way. And the fact that it’s YouTube-exclusive leads to an interesting emergent property: Alvarez can put all the famous pop music he wants on his movie’s soundtrack without paying for it, and lean on the platform’s licensing to keep from getting sued or taken down. Overall this is a project for diehard fans, though.

Being There (1979): Man, this movie. It’s beautifully photographed and well acted and it’s not for me. I posted on Peach (yes, Peach) after I watched it that it seemed like the most old-school Republican movie I had ever seen, and got immediately questioned on that by my movie-watching friends. I will concede that director Hal Ashby and star Peter Sellers were by no means conservative voters. I didn’t miss the satire of the political and media classes woven through it, which I am certain would later influence Armando Iannucci: the shallow characters’ hunger for a novel face and twistable platitudes, and their projection of political guile or sexual prowess onto the blank canvas of a simple man.

But the shape of the actual narrative is at odds with that intent. The protagonist—well, the focus character, this movie has no protagonist—is simultaneously a naif and a cypher who spends exactly one day outside the lap of megawealth in his life. But he’s not an antihero, and the camera loves him. A lot of the plot is taken up with mourning the passing of Melvyn Douglas’s titan of industry, and the mourning is impossible for me not to read as genuine! I think that in 1979, before Reagan, this movie would have carried a lot of nostalgia for an era of bipartisan harmony between rich white men. I placed it next to the preceding movie because I think “don’t expect to like ’em” applies again for me here. The suits Sellers wears here have aged beautifully, but that central takeaway has not.

Burning (2018): This is an adaptation of a Murakami short story, and I’m not particularly a Murakami fan; it is also a thriller that takes a solid eighty minutes—the length of some entire feature films—before the plot gets going. The full movie is 148 minutes long! But I was interested enough in the costuming and set dressing, which are meticulous and subtle, to stick with it and enjoy it. The core cast is fantastic, particularly Steven Yeun, and I was very glad that the frequently absent score kept from hammering home any of its ambiguous points.

For another take on Murakami that I really enjoyed, which does use music but lets you interpret the visuals, I recommend LeVar Burton reading “The Second Bakery Attack.”

Speaking of a long journey that involves both Mount Rushmore and Chicago, this is the last roundup I will begin drafting in Portland! I am on track to get pretty few movies on the list in October, but I am hoping to follow this with at least one entry like those from my original road trip out west eleven and a half absurd years ago.

Fast & Furious Presents: Hobbs & Shaw (2019): A motion picture I can only describe, and I apologize for this, as “nut-slammingly stupid.” It’s the Michael Scarn ripoff of itself. It’s as fascistic as a third-grader’s hypermasculine playground fantasy, lacking even the level of self-reflection I can credit to Predator (1989), and nudely calculated for maximum financial return; the frame might as well be stamped at the bottom with A SIGNIFICANT PROFIT SHARE BROUGHT TO YOU BY DWAYNE JOHNSON’S SEVEN BUCKS PRODUCTIONS®. Plus there’s an early set piece where the characters triumphantly pull off the exact same stunt that kills Johnson’s character in The Other Guys (2010).

I cannot justify why I paid first-run ticket price to see this movie, except that of course I did, it has “Fast” and/or “Furious” in the title. It does not live up to the best of its parents, but there are moments in the third act when Johnson’s proclivities almost transcend their setting. I can get behind inserting tough matriarchs and a badass Siva Tau into every movie you make! But nothing else here rises above the cash-extracting function of a boot stamping on a human testicle forever.

Gimme the Loot (2012): I cannot remember to take last night’s leftovers out of the fridge for lunch most days, but I skimmed a review of this mildly buzzy indie film before Barack Obama was reelected and my brain has been bothering me about seeing it ever since. So I biked around the corner and rented it! Thanks, Movie Madness.

Recommended, if not revelatory, especially if you like stories about graffiti dorks. Tashiana Washington (as Sophia) is a standout, and I appreciated that the director relied on her charisma without sexualizing her. This is the kind of movie where the characters’ schemes are well awry before they are even conceived, much less executed, and I sometimes have a hard time with that! I enjoy a bale of haywire, and it’s one thing if I don’t feel sympathy for the schemers—eg my delight in anticipating disaster on Arrested Development—but when I can guess how things are going to go and have to wait and wait for the characters to get there and feel bad, I end up wanting to crawl out of my skin. It’s like Leonard’s zap zap zap on the scale of ten minutes instead of two. Anyway this movie toes that line a little but pulls it out.

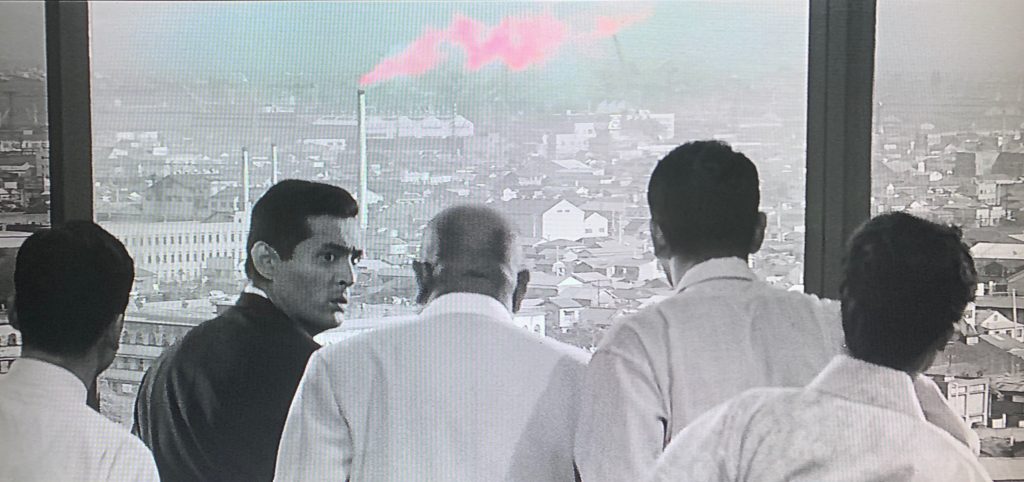

High and Low (1963): This was a pretty nuts-and-boltsy, unshowy police procedural with all its emotional fireworks loaded front and back. I continue to enjoy the sheer execution of Kurosawa’s movies and I will once again show you a photograph I took of my television to illustrate why.

There are like fifty people in this shot. When I look at it, my eyes jump to four or five of them: the man in sunglasses in the foreground, plus the two men on the left and the two men in captains’ hats on the right watching him (the suspect and the cops following him, respectively). One of the boat hat dudes has his face partially covered and one might not parse him at first, but the gist of “here’s our guy and here’s his tail” comes across immediately. The effect is even more pronounced when it’s moving instead of still.

Some of this is angle work and blocking, because the eye tends to look at people with their full faces turned toward you. Some of it is lighting—most of the other people have shadowed faces, and theirs are subtly spotlit. That must have been fucking complicated, but I can at least imagine how you’d do it.

What took me days to figure out is the focus. All of those guys are nice and crisp, in their various positions, so the depth of field isn’t super tight. There are some people way in the back who are blurry, and that makes sense too. But then there are people like the dancer in sunglasses just above the boat hats. He’s blurry, and he’s closer to the lens than the cop in the Hawaiian shirt. That does not make physical sense! Lenses do not work that way! In 2019 this would be trivial to throw at a computer, but there was no cheating in 1963.

I finally determined that they didn’t do selective lens-smearing or tilt-shift or rear projection or anything like that—they just hung a super thin scrim between those mirrored columns, pulling out an old theater trick to subtly dial down the contrast and focus and brightness in the back. That must have made the lighting even more complicated, because you have to light a scrim from an angle to get that gauzy effect, but they did it and it worked! All because Kurosawa (and his cinematographers, Asakazu Nakai and Takao Saitô) cared about making this shot read fast and well.

Minding the Gap (2018): I wasn’t intending to watch two self-shot documentaries about young people in a row, but I stumbled onto this (on Hulu!) and got drawn in. It’s an extraordinary movie, one of those I feel most motivated to recommend in my entire 2019 list.

It was really affecting to me to figure out the nature of the film as I watched it, but I don’t want to recommend it without a content warning: this is a movie about abusive fathers, and the people their sons become. That makes it sound like it’s hard to watch, but while certainly some of it is difficult to sit with, it’s never cruel to the audience. Most of the film is charming, goofy, and evocative, with gorgeous bursts of wordless beauty and arresting glimpses into consequence, or into the challenges its creator faced. And the musical conclusion pierced me right through.

The other thing is that this is a skateboard movie. I never had a skateboard when I was young, though I adopted some distinctly skateresque clothing choices. I didn’t have the opportunity to learn to skate, really, but even if I had I know I wouldn’t have had the patience or the grace. I admire it very much as a skill. It’s not as if skate videos are a new phenomenon, but Bing Liu is a good enough at those alone to grab your attention. I was impressed by Point Break (1991) getting its surf shots through a crew of seasoned professionals who got paid presumably well to risk their necks. The skating sequences in this movie were shot by one kid. One kid.

Destroy All Monsters (1968): Despite its awesome title, clear potential, stellar production crew and mighty budget, I’m afraid, my friends, that this movie is not very good. The traditional way to make a kaiju movie bad is to skimp on the expensive monster effects sequences by putting in lots of plotty stuff focusing on concerned humans no one cares about. This movie clearly spent gobs of money on effects shots, but almost none of them include the frickin monsters! There are ten minutes of slow, majestic rocket landings for every minute of monster screen time, which means this movie shorts both them and the audience. This is a movie featuring Mothra where Mothra NEVER TURNS INTO A MOTH.

There are great moments, including a shot of the Arc de Triomphe being demolished while a reporter declares “ze Arc has fallen… and soon, Paree!!” and also Godzilla contemptuously slapping down Ghidorah’s head like a deflated basketball. And if there are too many shots of miniature vehicles, at least the minis work is advanced and great! But while I only know a tiny bit about the movie’s production history, it’s very clear it came from people who were just done with giant monsters after fourteen years. I just realized as I typed this that it’s an Avengers movie. Of course it was doomed.

In conclusion, at no point in this motion picture does anyone shout “destroy all monsters!” or indeed make any attempt to destroy all monsters, and on that, your honor, the offense rests.

Spider-Man: Far From: Home (20:19): You can probably skip down to Yojimbo (1961), this part is a nerd trap and I’m still caught in it. Also it’s full of spoilers, if you care about that.

This purports to be a movie about the consequences of Tony Stark’s death, but even more present are the ghosts Stan Lee and Steve Ditko, who created Spider-Man together and both died in 2018. Whatever any given audience thinks of Lee, the people behind the Marvel Spider-Man movies were clearly big fans; the license plate and wrestling poster Easter eggs alone are indication of that, and the big hallucinatory illusion sequence in the second act is a big ol’ fanvid drawn straight from the Lee/Romita on-page experiments of the early 70s. I think it does Doctor Strange, another Lee/Ditko creation, better than Doctor Strange (2016) did. Sooo when you include a subplot about disgruntled people whose work was subsumed or absorbed to promote one man’s self-made aura of genius, it’s hard not to see another side of that too. There might be a movie out there that can sell me on the idea that the correspondence was deliberate, but as much as I enjoyed it, Far From Home is not that.

There’s a lot going on in the movie thematically and none of it quite gels. Is this a movie about people needing to move on? That topic keeps coming up but never gets an emotional climax. Is it a movie about how drones are bad? It’s certainly not the first Marvel film to express that unease, but why does it go unremarked that Tony Stark apparently built a global pinpoint-assassination system just like the one Steve Rogers was willing to die to destroy in The Winter Soldier (2014)? Is it a movie about whether Peter Parker—who, in current comics canon, operates a multinational tech corp in very Starkian fashion—is meant to step into his dead mentor’s role? Kind of, but that shouldn’t even be a question the MCU has to ask, because the MCU already has an established born leader and tech wunderkind for its next phase of superheroes. Their names are T’Challa and Shuri!

Is it a teen road movie? No, it backgrounds all of that in favor of very expensive-looking effects sequences. Is it a love story? Almost, almost. Tom Holland and Zendaya have about three scenes together, and they’re electric! Those two people are very good at acting! You have to have something special to actually sell me on a Peter/MJ romance in two thousand damn nineteen, and they did, but in true Sirius Black fashion, we barely get to glimpse the good stuff before it’s gone. A big flaw in the movie is how it continues the timeworn MCU tradition of failing to foreground its women; it needs not only more Zendaya, but more Cobie Smulders, and any at all of Jennifer Connelly, and more Marisa Tomei. How are you going to make a movie set in Venice with Marisa Tomei and ghost Robert Downey Junior in it and not even throw in a sly reference to Only You (1994)?

Anyway, since I started drafting this post the movie made a billion dollars, so Marvel/Columbia/Sony are probably pretty happy with Jon Watts and his directorial choices overall. I just liked Homecoming so much, and thought this showed such potential to be a movie specifically suited to my tastes, that I have a hard time not wrestling with the things it wasted and missed. NERD TRAP OVER.

Yojimbo (1961): Man, just look at this.

There are eight people in this shot, where one of the contenders for town boss is receiving Toshiro Mifune’s ronin and wheedling for his services. I didn’t do anything special to grab this frame—I just paused my player and took a photo of the TV with my phone, like a monster.

For the majority of people, color is a critical component of the way we separate shapes from each other, figure out what to pay attention to, and—like it or not—assess others. This image has no color dimension. But because its costume design is brilliant, my eyes immediately parse each person in the shot, and it’s even easy to grasp their ranks: the boss and his wife have the most ornate clothing, the ronin wears simple solids, and the background lieutenants each get a distinguishable but undistracting pattern. Because it’s blocked well, I know right away that Mifune is the center of the scene, with everyone else’s attitude cheated toward him. I happened to catch a frame where most of the lieutenants are looking down as they settle in, but the three principal characters always have their faces in full view or profile, so your brain can follow the conversation between them without the need to reverse between close-ups.

It’s fun to be able to break that out after the fact, and it’s even more fun to get picked up and carried along by it in motion. There’s all kinds of STUFF in Kurosawa movies: moving weather, moving fabric, bold expressions and exaggerated gestures and all kinds of people on the screen. Heck with minimalism! It’s great when the frame is busy, as long you can do it in a way that works for the viewer instead of against them. Anyway this movie is good and cool.

Predator (1987): I love Alien (1979) and that franchise has long been a point of comparison against this one, so I decided to watch this. I didn’t like it. All right, John McTiernan, I hear your latter-day argument that this movie has some satirical intent behind it: the scene in which the bulging shout-men clear-cut an acre of rainforest using infinite bullets actually does trample right past power fantasy into grand display of impotence. It is goofy, but what does it end up saying by the end? That when the mechanized instruments of murder fail you, you must turn to… less mechanized instruments of murder? That beneath the ugly mask of sport hunting is… a face that is also ugly? I don’t buy it! This movie wants to stab its cake and shoot it too.

My favorite part was the special effects, which I think have now crossed a line from “dated” into “gloriously retro.” I spent most of the runtime thinking about the ways in which the Predator is shown to be a peerless hunter of men, to wit:

Damn, Arnold, you really skinned your teeth on that one.

Point Break (1991): See, with this one I can give credence to a certain archness of regard! Among Kathryn Bigelow’s other movies, I have only seen The Hurt Locker (2008), but that alone gave me reason to think she had a more nuanced understanding of masculinity than the other John McTiernan movie I have seen (Die Hard [1988]).

Contemporaneous reviews of this movie seem to have missed the homoerotic frisson that overlays the entire thing, not to mention the way the film keeps rolling its eyes at the incompetence of the FBI characters and the surfer gang’s bullshit philosophy. This is a movie shot by someone who had already watched many men’s eyes glaze over as they stopped listening because they believed they had something more important to say. The silent camera, in fact, plays with everyone here like a superior dance partner, and that’s one thing the reviews did notice—technically, the surfing and skydiving and chase sequences must have been fucking hard to shoot! There was no bullshitting with CGI in 1991, and no infinite digital storage either. For every perfect curl we get to see someone riding through in slow motion, someone else was doing the same thing, holding a camera, with a limited amount of celluloid film in a canister, backwards.

I loved this movie even though it had almost zero women in it. And having watched it, I’m now convinced that Bigelow invented the so-called Sorkin walk and talk!

Millennium Mambo (2001): I picked this up because The Assassin (2015) made me interested in Hou Hsiao-Hsieh; I didn’t realize they both starred Shu Qi. I know film is the voyeur’s art form or whatever, but this really leans into that, I’d say even more so than something like Caché (2005). It’s like watching a play through a keyhole: the action is mostly confined to a few locations, shot with long lenses and takes that limit camera movement to little more than the occasional pivot. Sometimes there’s a table in the way of the shot, sometimes a closed door. I felt like the camera and I were both trying to lean forward and peer around the obstructions, but not in a frustrating way. It’s not just obstruction, after all—it’s bokeh and parallax, shot along long axes, just like Mackendrick liked to say. Even when you can’t see what’s happening, your eyes aren’t bored.

In terms of other movies I’ve watched this year, I was reminded of Days of Being Wild (1990), but even more so of Morvern Callar (2002)—in part for its focus on an enigmatic young woman, but also for all the rich, soft light and texture and color on the screen. I honestly don’t know if there was some kind of film stock or grading process that they have in common, but it summons the look of the early 2000s even more than the candy bar phones or club music or all the cigarettes.

I’m getting all wistful now! 2001 is the year I started this blog—please do not verify this—and I had so many ideas about the future, and no idea at all. Anyway, I am also delighted by the fact that in the second scene of this movie, one of the characters wears a shirt that just says KISS, while the other’s shirt just says ARMY.

Submarine (2010): I can’t believe I procrastinated on watching this for almost a decade. I love Richard Ayoade, I love Harold and Maude (1971), I love teen movies, and I like Wes Anderson a lot, so it was a foregone conclusion that I would love this. And I did. If it had just its fleet and startling pacing, or just its frank sense of humor, or just Sally Hawkins (a generational talent, an utter badass, someone who makes acting actually seem important), or even just its pinpoint costuming choices, it would be worth watching. But it has other things too! Among them, period-accurate but unnecessary homophobia, which disappointed me a bit in the midst of all this delight.

Anyway, make more movies, Richard Ayoade. I don’t want to spoil the very first frame of (the American release of) the movie for you, but it’s worth looking up.

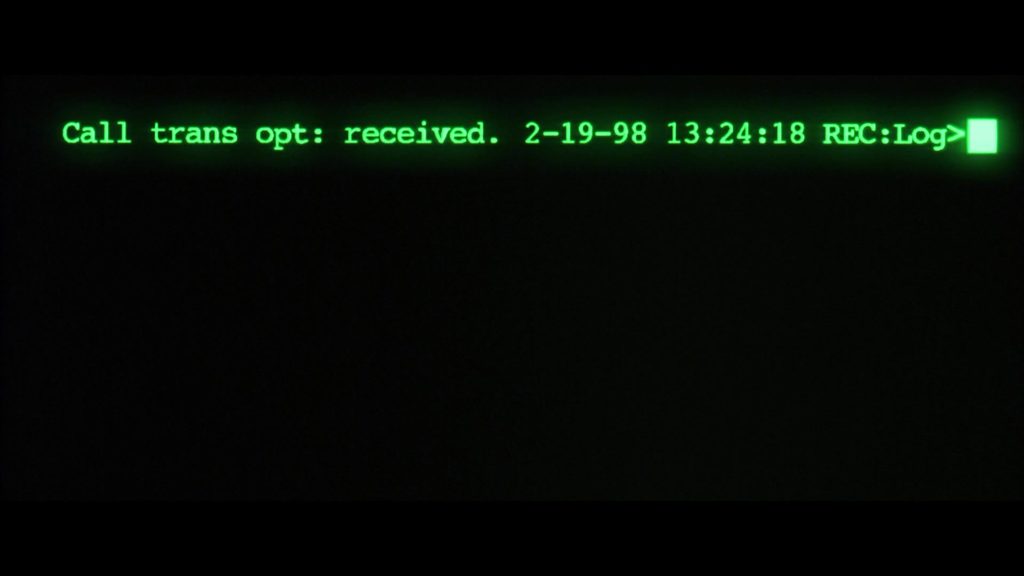

The Matrix (1999): Rewatch, of course. Man, speaking of opening frames.

Years ago, my friend Avery pointed out to me that the “red pill” isn’t just a metaphor used to promote violent misogyny after being co-opted from a woman—it’s been read as a pretty explicit allegory, in the film itself, for a hormone pill. I thought about that and found it pretty convincing as an authorial intent, especially after both the creators came out as trans, but this was the first time I’d watched the movie with that framework in mind.

And when you look for it, it’s everywhere, from the first thing you see on the screen to nearly the last. One of the first things Neo says to Trinity is “I thought you were a guy,” to which she replies “most guys do.” The character of Switch visibly presents different genders in the Matrix and the real world. The Matrix itself is described as a prison made of… binary. The Oracle tells Neo to “know thyself,” and that he’s waiting for another life. Even in the climactic fight between Neo and Smith, Smith holds Neo in front of a train he calls “inevitability” and taunts him by calling him “Mister Anderson.” Neo’s response—“my name is Neo”—isn’t just a good retort, it’s a rejection of the identity he was assigned at birth.

I have a long and complicated history of regard for The Matrix; it made a vast impression on me, but even in 1999 I could see how it seemed to me to center the experience of a generic privileged man, and how much it swiped from other creators without offering much credit. The fact that it got appropriated by self-righteous nerds and by shallow philosophy and pop culture reference gags, and that the sequels were… the sequels, didn’t help me feel great about having latched onto it myself. But this lens for it thrills me, because it takes the movie back from its worst fans and makes it vital, relevant, and still radical twenty years on. There was always something in there that was more than the sum of its parts; it just took the patient education of queer people in my life to let me see it.

Chungking Express (1994): This is basically two short films—and was almost three—one about an oblivious young police officer blundering onward from a failed relationship while eating all the food in Hong Kong, which is followed by another about an oblivious young police officer being forced to move on from a failed relationship by a manic pixie terrifying stalker. All together I found it a little clunky, and there’s barely a thread of connection between the halves except in their themes, but the second half—the Faye Wong/Tony Leung half—is a nervous delight!

Also, the thing I linked up at the top of the previous paragraph is a video of Quentin Tarantino talking about the movie, in the comments of which I learned that Tarantino’s face accidentally introduced Barry Jenkins to this movie and to Wong’s work. There have now been two good things in comments sections on the internet.

Bad Times at the El Royale (2018): This movie was cast well, and shot well, and designed well, and soundtracked well, and again, cast so well that it bears repeating, and I got to the end of its long runtime without any idea of what it was about. It’s a thriller without a relevant anxiety to play with, and it wants to be a noir movie, but it doesn’t really have a Thou Shalt Not with which to punish its characters. It spends minutes on end detailing the central conceit of its bi-state hotel setting, and then never actually uses that for anything. Speaking of Tarantino, it looks a lot like one of his later movies, but without any of the moments Tarantino takes to bust out into gleeful, visible artifice.

All of which is to say I wasn’t offended by this movie, and maybe I’m missing something, I just don’t know if there’s a there there. It did, however, confirm my strong parasocial relationship with Cynthia Erivo (lately of Widows [2018]), and one part that made both Kat and I yelp was spotting Manny Jacinto from The Good Place in the credits. He grew a mustache!

(Updated 0734 hrs because I forgot to insert the picture!)

The Red Turtle (2016): By contrast, I did a lot of observing composition (and color, and texture) in this movie, which is beautiful but I think holds itself a little apart from you. Part of that is its constraints: no dialogue, no narration, no explanations at all, like a wordless picture book. The characters don’t even have names. For me, that blunted its emotional impact as well, but it was very beautiful to watch.

They did pull out one particular and effective trick I haven’t really seen much in 2D animation. Usually, even when the 2D is all digital rather than cel painting, the “flatted” color areas are in fact flat, with maybe some highlights and shadows thrown in for depth; details are done with line work, and flatting is a separate process stage done quickly and by lower-level animators. If you see texture and detail within a colored space, it’s probably on something static like a background that only has to be drawn once. In this shot from Spirited Away (2001), Chihiro and the car were drawn by animators, where the idol and the trees were done by static painters. See the simple colors on her shirt compared to all the variation on the stone?

Instead, The Red Turtle takes advantage of its digital nature, attaching texture to everything and letting the computer do the work of keeping it consistent with movement. It’s like film grain, but you can see in this shot that it’s applied differently to various surfaces—the upper area of the turtle’s shell has less texture than the parts below the water.

They do some other fun stuff too: using the surface simulation usually applied to fabric or water in 3D animation for foliage here, for instance. There’s some cool ligne claire influence going on, and Lucy even pointed out a couple of nods to Moebius. Simple story, visual feast.

You Were Never Really Here (2017): My second Lynne Ramsay movie, after a fifteen-year time jump in her career. I feel like if you have heard of this movie then you know it features a lot of violence, including violence against children, sexual and otherwise. It’s hard to put that in a genre story in the 21st century without seeming exploitative yourself, and I don’t know if this movie entirely avoids that.

All that said, holy fucking shit, I understand better why people are so reverent about Ramsay now. Fleet without skimming, enigmatic without distancing, clever but not ostentatious, observant but not voyeuristic—or at least not catering to the voyeur in all the expected ways. The crew’s stylistic watchphrase was apparently “heavy camera,” and the implications there are carried through.

Ramsay does this thing in common with Alexander Mackendrick that I might have mentioned before. This movie had sequences where a moving subject is obscured for most if not all of the shot, but I never felt confused or lost because my eye was guided along their path. I haven’t quite parsed it out yet, but I think it might be something like this: you catch the subject at the start of the shot at a rule-of-thirds line, as the point of focus, entering with movement; you keep the camera centered and focused on them as they move into obscurity, through a crowd of people or behind traffic; and you catch them out of it on the other side, at the opposite screen-third focal point, emerging into perfect focus and giving the audience a pleasing “aha” of facial recognition. You can convey depth of field, parallax, atmosphere, tension, and action all at once in a simple shot, but it only works if you have the technique really nailed down. Eventually I will find some clips that demonstrate what I’m talking about and then come back and compare them to see if this theory holds up.

Kat sent me an article that bothered me, so I wrote a post for my employer’s blog about some of my favorite hobbyhorses. (I like my job; let me know if you want to work here.)

If there’s one thing I should have seen staring at me in last month’s roundup, where I raved about Barry Jenkins, Wong Kar-Wai and Jordan Peele, it is that if I want to find work that is exciting and engaging to me and made by people who came out the gate really strong, I cannot rely on movies made by (straight cis) white dudes. This is hardly a new concept, but that does not make it easy to put into practice. I’m still trying.

Also, I regret to say that I didn’t watch any movies I hated this month. Sorry, Last Month Concluding Paragraph Brendan.

Get Out (2017): It’s Auteur Month on the Roundup du Filme!! It’s not actually Auteur Month on the Roundup du Filme. My understanding of this movie from its first trailer up until last month was that it would jab directly into the areas that are hardest for me to bear in fiction; I only decided I was brave enough to watch it after I survived Us (2019) without losing my mind. One cool thing I noticed seemed like a twist on a thing I referenced back in January.

In Night of the Living Dead (1968), as required by its chief technical constraint, the scenes of respite and interpersonal conflict are all shot on a tripod; it was the only way to hold the camera while recording sound. When shit goes down with the zombies, the music swells and the camera goes handheld, emphasizing the chaos with the shaking frame. Many, many people have relied on that jitter-means-jittery technique ever since. In Get Out (2017), the opening and all the interpersonal stuff is shot handheld—not shaky, but not steady either. That takes advantage of the other implication of handheld shots, which is intimacy within emotional relationships. It’s only when you’re watching something that foreshadows or explicates the movie’s horrors that you get a smooth dolly or a static frame, and many of those are wide shots from a distance. Instead of chaos up close, you get dread at a helpless remove, which (SPOILERS) ties into the protagonist’s experience. I don’t know if Peele was the first to do that flip, but he does it well.

Homecoming (2019): Okay, maybe it is actually Auteur Month on the Roundup du Filme. I’ve seen Beyoncé in concert, on the Formation tour in St. Louis in 2016, and it was a tremendous experience. For someone who does not have a background as a composer, a writer, a designer or a cinematographer to demonstrate her level of specific creative control is interesting; this concert doc is styled “A Film By Beyoncé” and I don’t think it’s just puffery.

The popular discourse goes like this: 1) “you have as many hours in the day as Beyoncé,” 2) “no, Beyoncé’s wealth grants her time via the labor of others.” The thing is, though, even if I had all her resources, I am certain that I would not have her reserves of will. The parts of this movie that document the work of creation leading up to the performance make that clear. She was in a rehearsal space hashing out the initial concepts of the show within two months of giving birth, to twins, and the work of expansion and refinement continued right up to the opening performance, plus the following week until its closing one. I have no illusions that I want to hang out with Beyoncé. But while I do not believe in the divine right of royalty, sometimes I understand why people did.