“Otnes abandoned the narrative style… The move set him apart from other commercial artists of his time, and his willingness to embrace the abstract and chaotic nature of collage put him in high demand during one of the most turbulent decades of American history.”

— The Saturday Evening Post, 2015

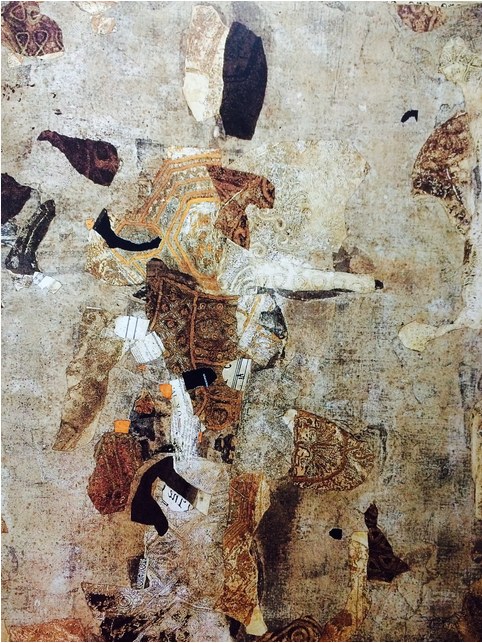

“Fred Otnes brings to his collage paintings a classical refinement and control that makes poetry out of chance pictorial effects. He dips into early Cubist collage techniques, touches Florentine and Renaissance bases, and reverses Dadaist chaos into gorgeous homages to order.”

— Maureen Mullarkey, 2002

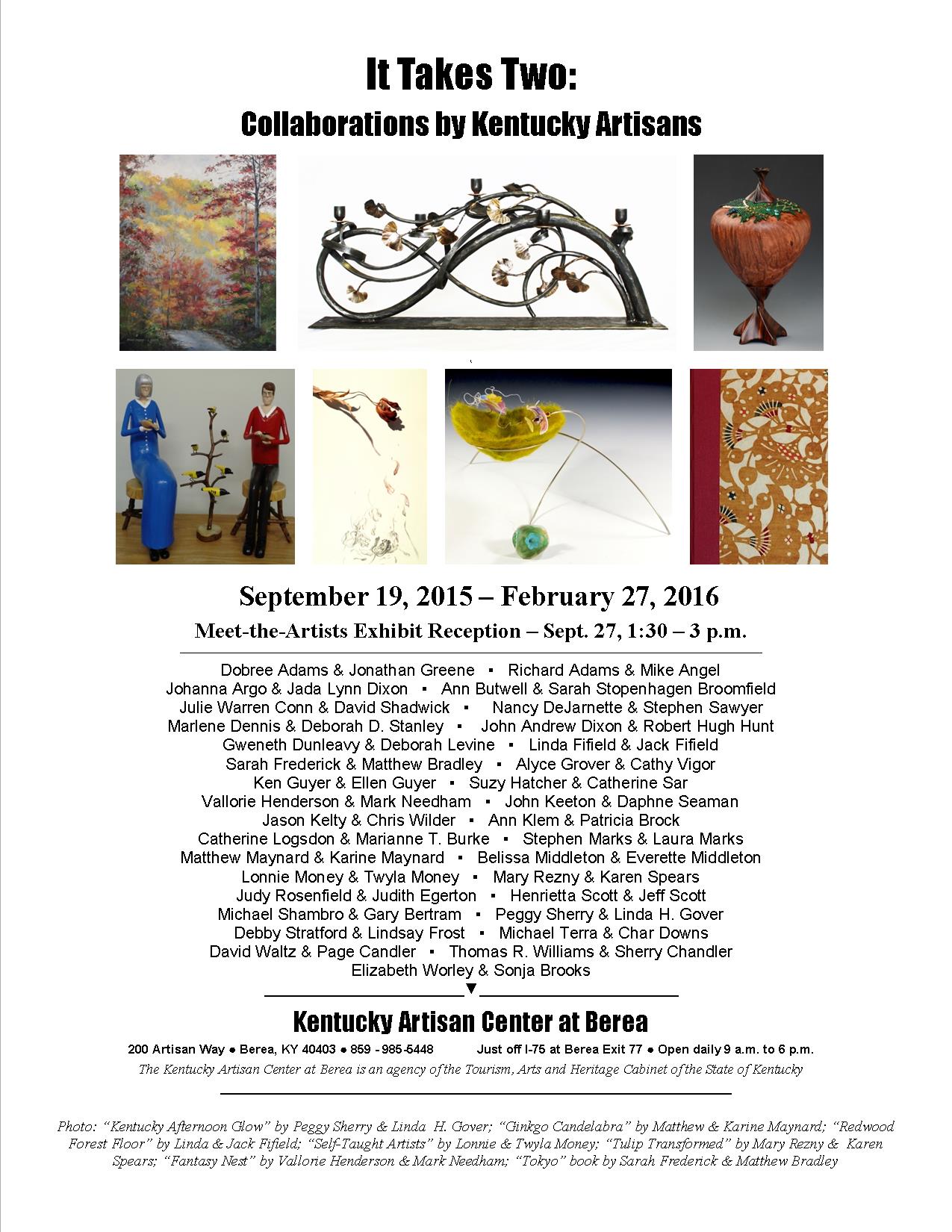

I just learned about the death of artist/illustrator Fred Otnes. I tend to focus here and in my own practice on the acknowledged masters of fine-art collage, but Mr. Otnes certainly had a greater influence on me during my formative years and during the period of my life devoted to “making it” as an independent illustrator and designer. He is rarely included among the seminal figures of 20th-century collage, but he should be. Allow me to back up a bit and reveal some of my own story.

In the 1960s I had four different art teachers in four years of high school. I resist being unkind, but each one of them was worthless. I had some talent, so there was no reason to spend time with me. I was left to fend for myself, because, apparently, it was more urgent to actively babysit the class goof-offs. By sixteen I was investigating the available correspondence coursework. No one thought to tell me about the Dayton Art Institute in the closest big city. I don’t think I even realized how desperate I’d become. What others might have viewed as crass merchandising was a Godsend for me. I responded to an advertisement from the Famous Artists School and completed the test. A representative actually paid a visit to discuss the home-study course that would provide the fundamental art instruction I’d been missing, and I begged my parents to let me give it a shot. They said, “Okay,” and I am grateful for this simple consent — access to legitimate art educators would be mine. I acknowledge now that their “Course For Talented Young People” was a marketing experiment, an attempt to leverage the successful adult course with a younger demographic. That meant nothing to me at the time. This was the school endorsed by Norman Rockwell, and I was a charter student! Although my Mom eventually had to cajole me into keeping abreast of the challenging lessons, a sea change had occurred. I was at long last formally introduced to the world of fine and applied artists. Among those that impressed me most was someone named Fred Otnes.

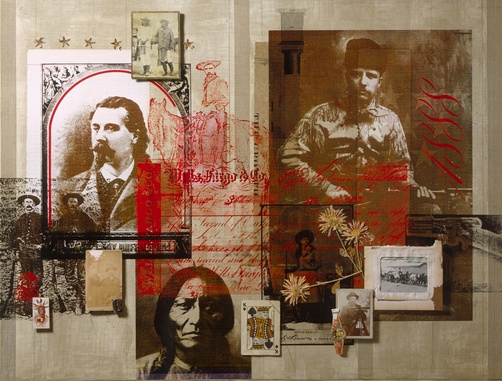

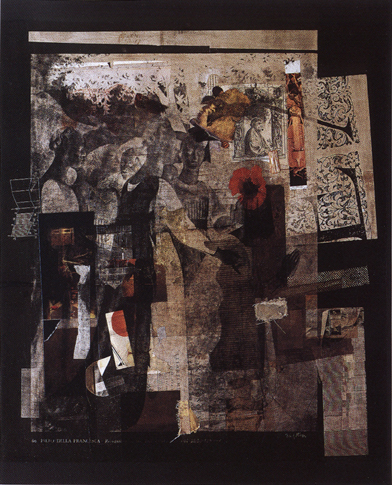

I was a peculiar kid who got more excited about magazine illustrations, corporate trademarks, television animation, and the Sunday comics than I did about “museum art.”  The work of Otnes touched me in a way that would take decades for me to unravel. In my youth, not being able to figure out how an artist created something was usually paired with disinterest, but his work affected me in the opposite way. His graphic synthesis of images, engravings, diagrams, and language exposed a realm that I could aspire to enter. Even as an experienced pro, I continued to find his technique mystifying. I was relieved when legendary illustrator Mark English said, “I don’t even know how he did them, the mechanics of printing, photography and all the things he did to put them together.” Suffice it to say that in a profession biased against the creative explorer, Fred Otnes braved a path that few, if any, realized was there, successfully made it his own, and became one of the most distinctively recognizable, highly honored applied artists of his generation.

The work of Otnes touched me in a way that would take decades for me to unravel. In my youth, not being able to figure out how an artist created something was usually paired with disinterest, but his work affected me in the opposite way. His graphic synthesis of images, engravings, diagrams, and language exposed a realm that I could aspire to enter. Even as an experienced pro, I continued to find his technique mystifying. I was relieved when legendary illustrator Mark English said, “I don’t even know how he did them, the mechanics of printing, photography and all the things he did to put them together.” Suffice it to say that in a profession biased against the creative explorer, Fred Otnes braved a path that few, if any, realized was there, successfully made it his own, and became one of the most distinctively recognizable, highly honored applied artists of his generation.

For many years, through the Illustrator’s Workshop, Otnes was a teacher and mentor, and, like others in the field, spent his later years expanding his personal style as a gallery artist. Whether applied to editorial or commercial use, the creations embody his profound respect for subject matter. If there is something elusive in his work that will continue to inspire me, it is this — I shall always hold in high regard the sense of “reverence” he brought to each layered plane of expression, to every choice of color or texture, to the symbolic meaning of each ingredient, and to the aesthetic harmony of the whole.

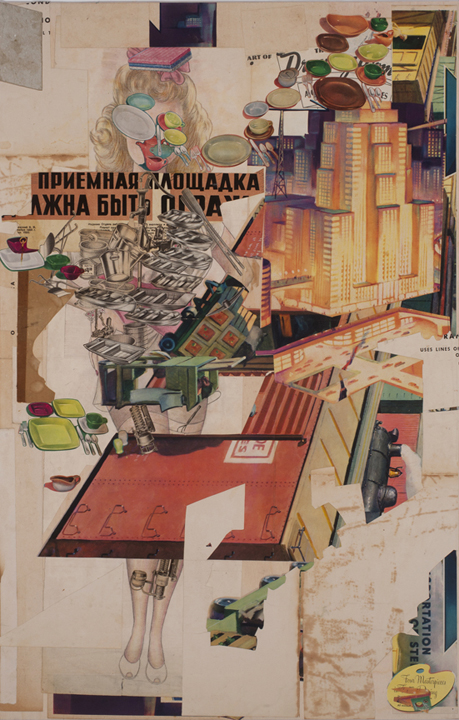

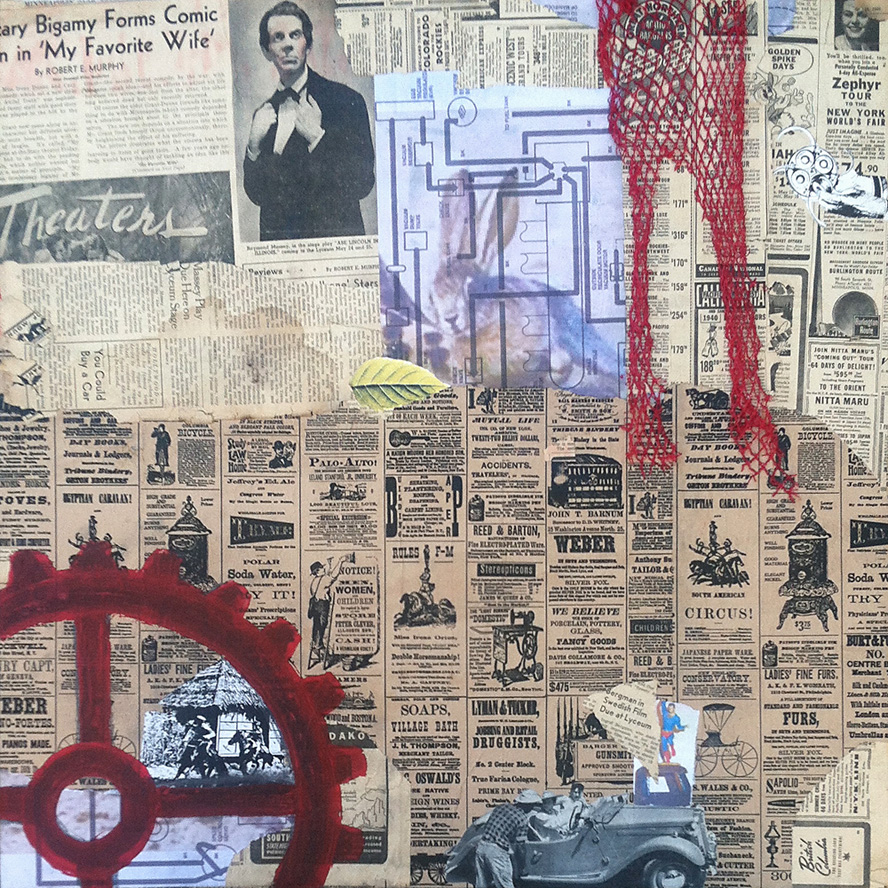

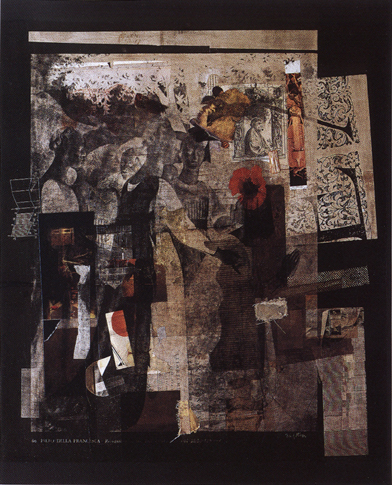

The Day Mussolini Dies . . .

Saturday Evening Post illustration by F Otnes, 1966

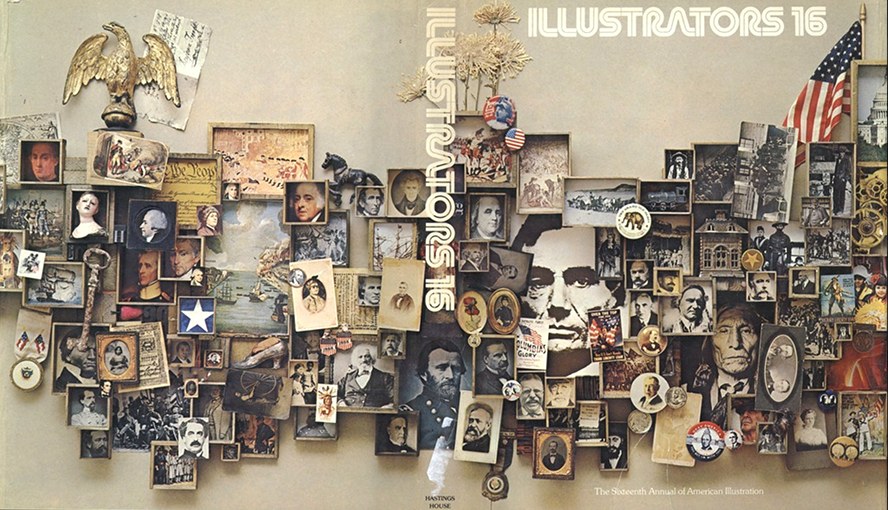

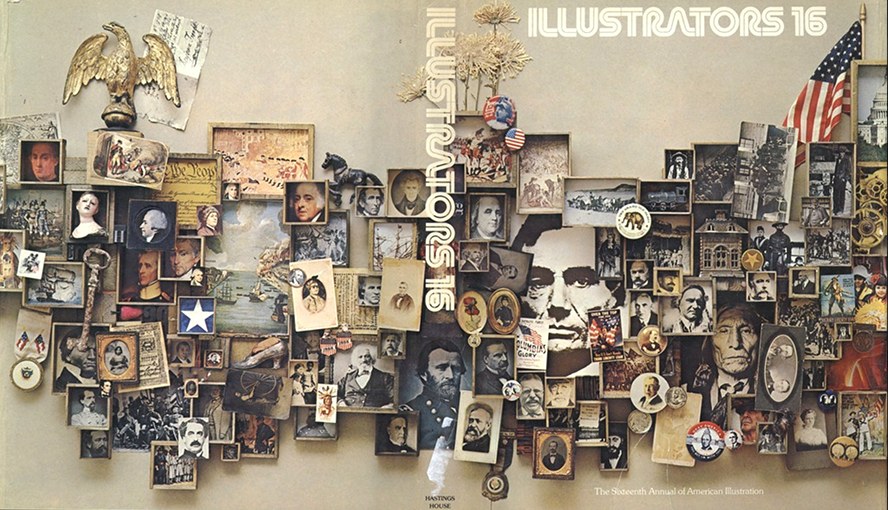

Illustrators 16

Society of Illustrators Annual cover by F Otnes, 1974

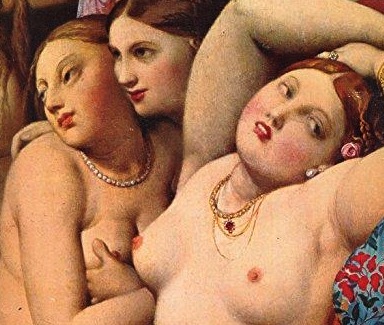

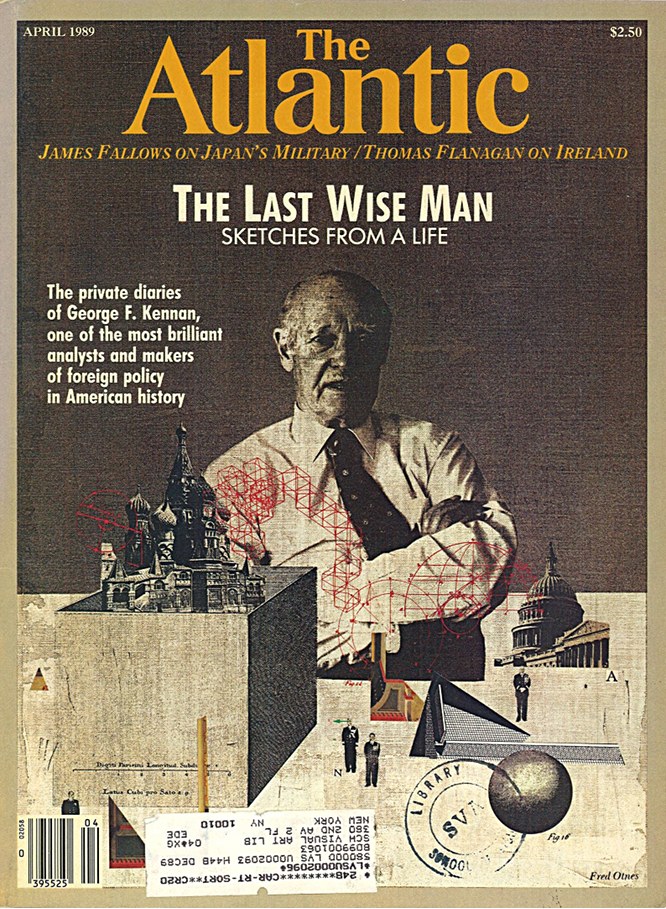

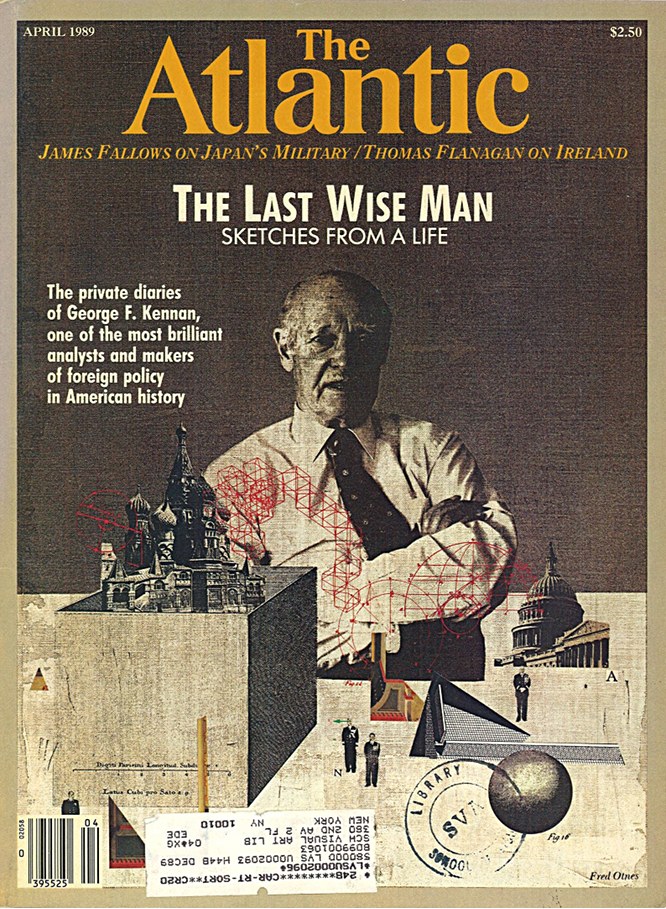

The Last Wise Man

Atlantic cover by F Otnes, 1989

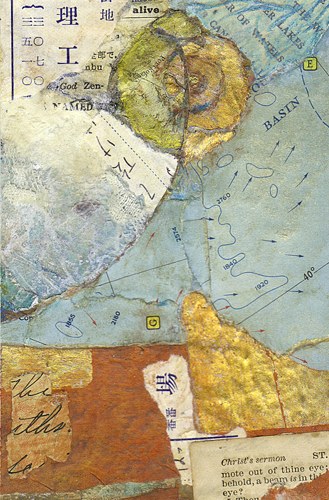

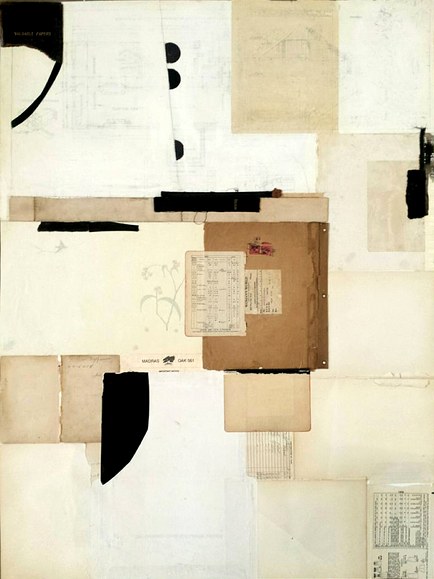

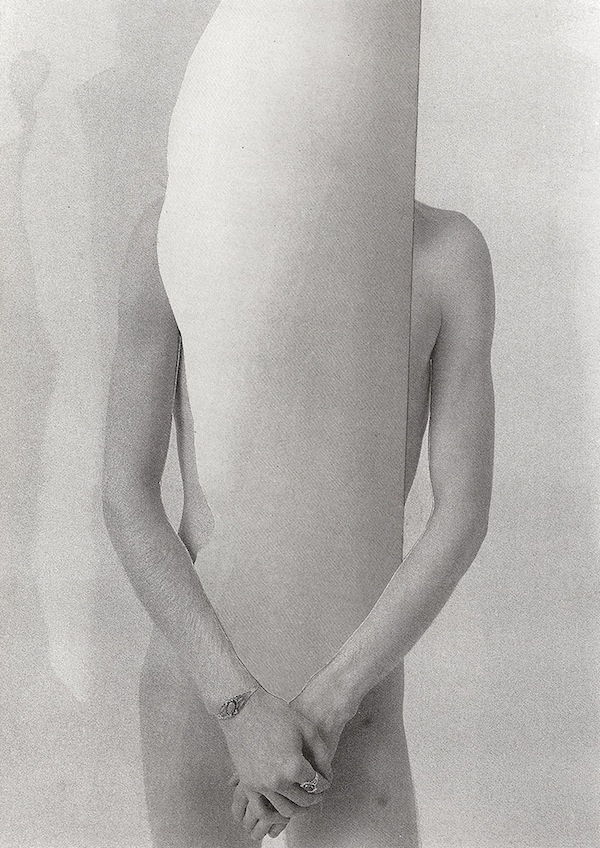

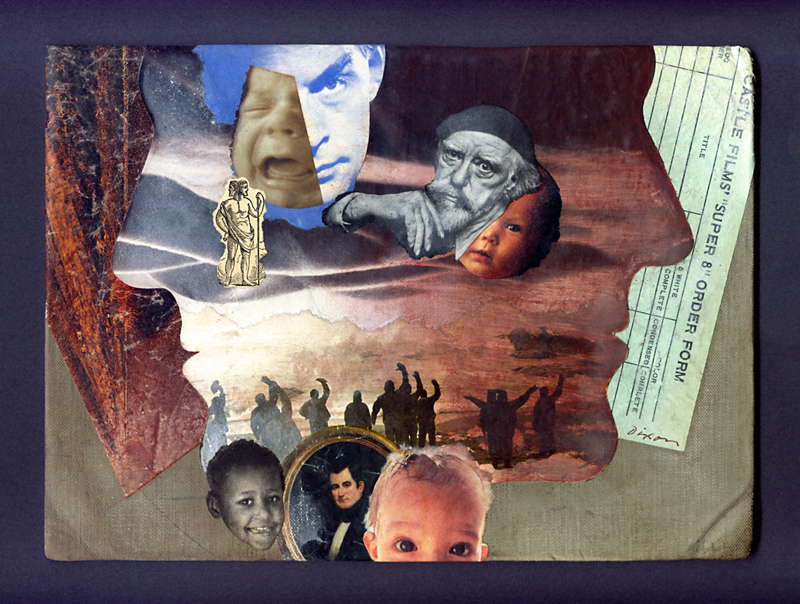

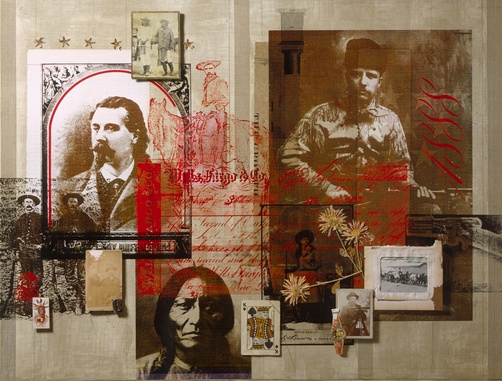

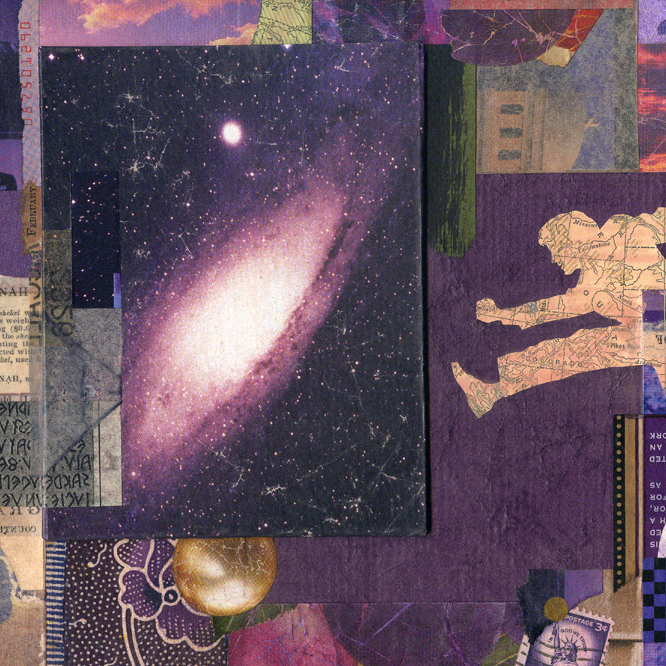

(title unknown)

National Geographic illustration by F Otnes (rights managed)

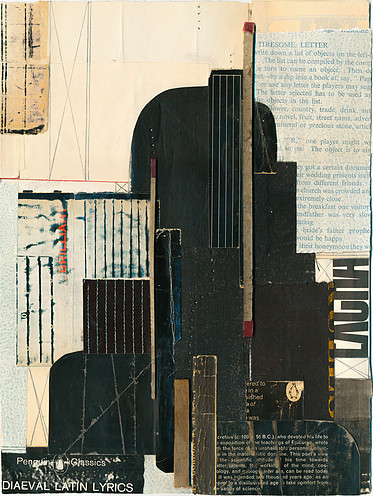

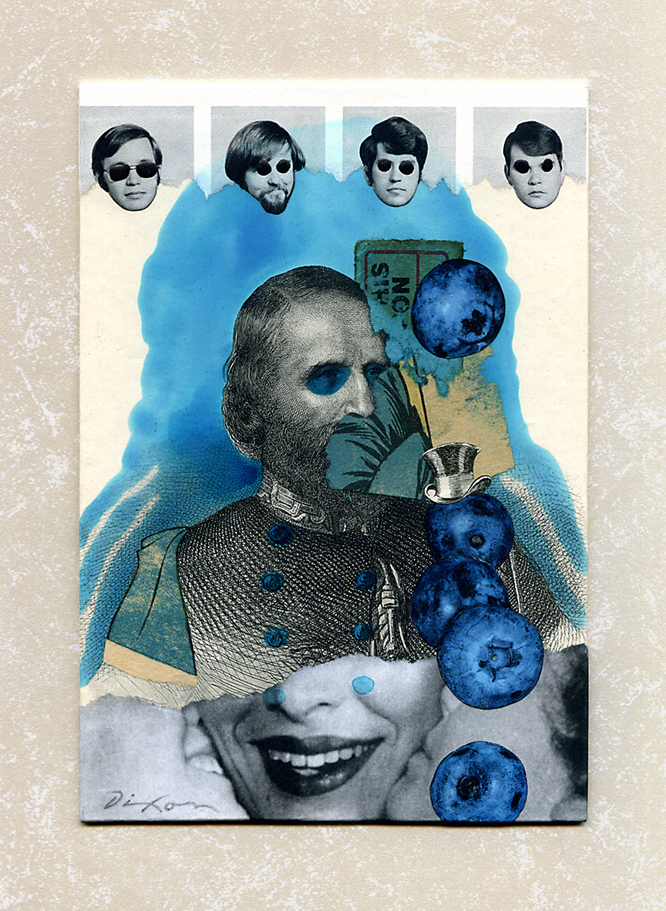

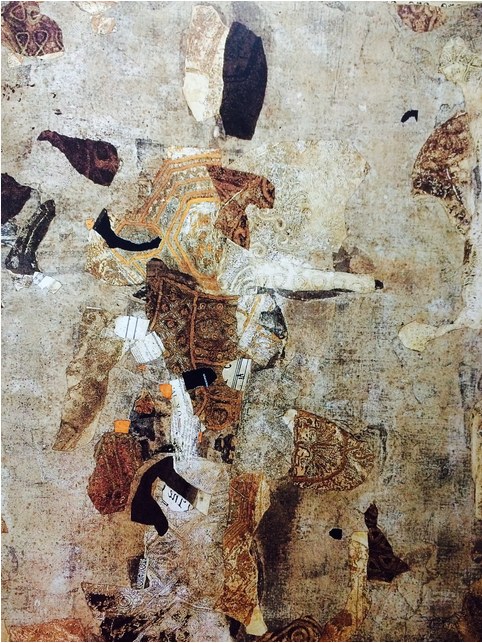

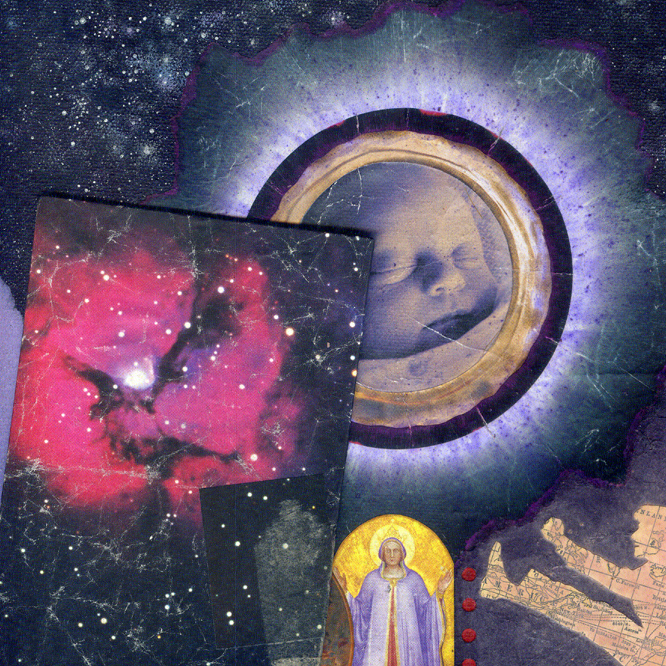

Piero

traditional collage by F Otnes, 1994

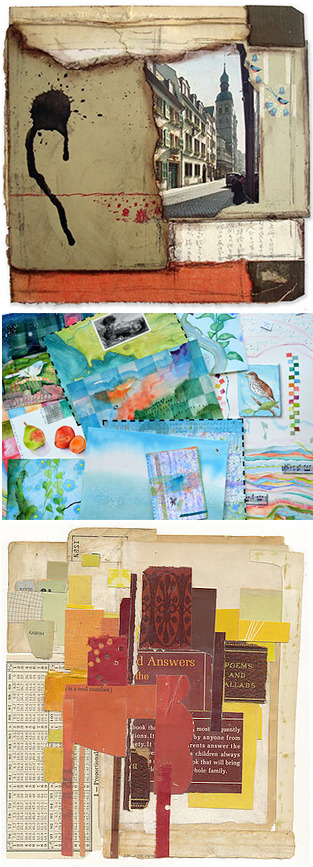

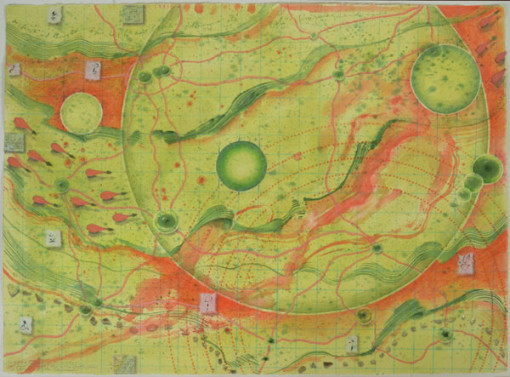

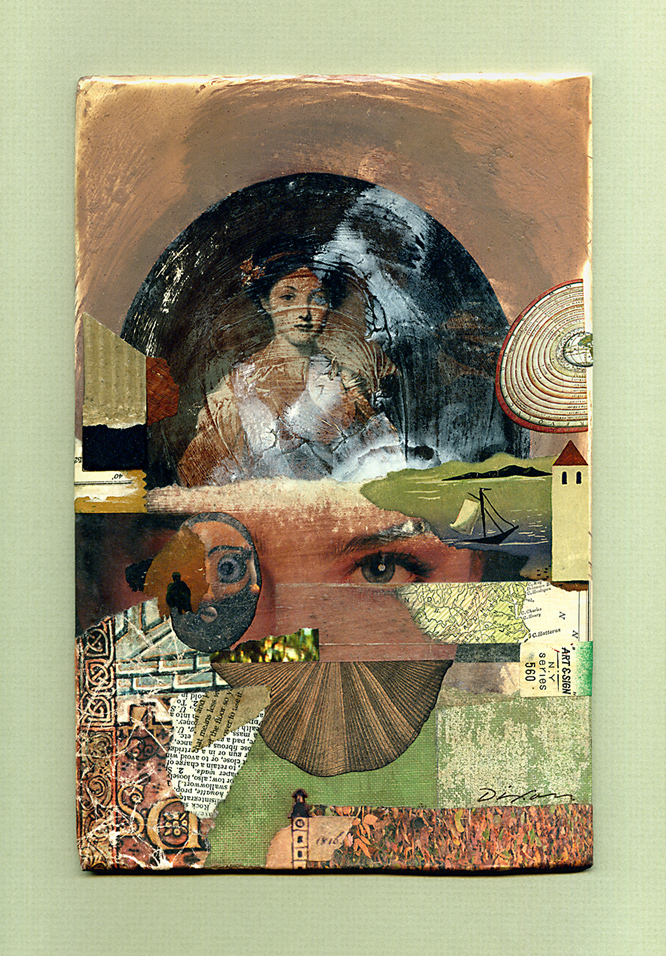

A Tragic Princess

collage painting by F Otnes, date unknown

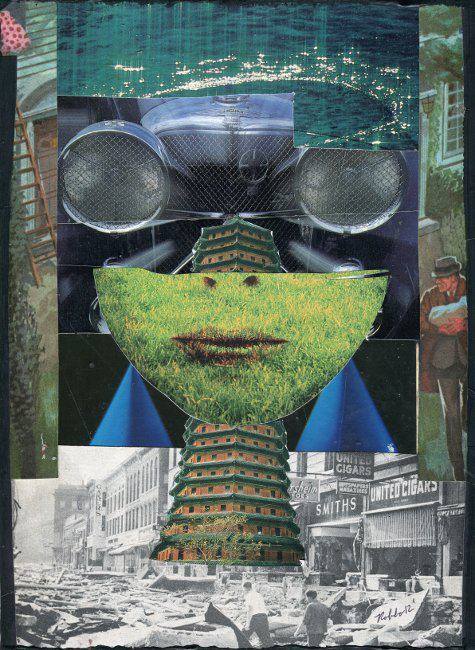

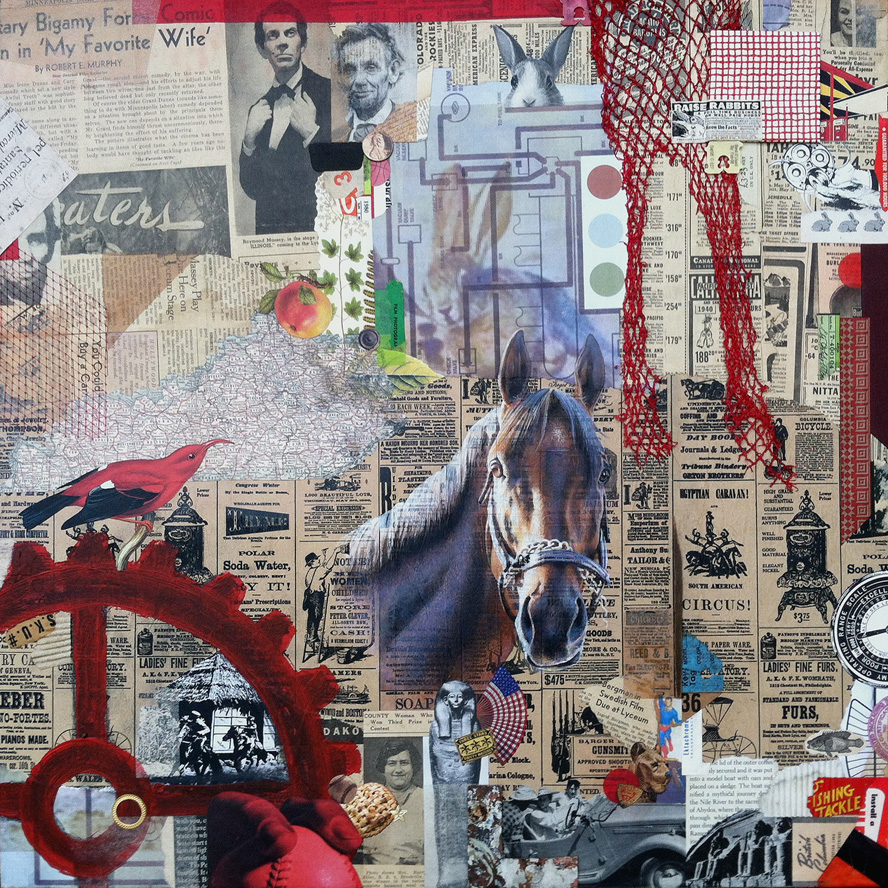

Liagre

collage painting by F Otnes, 2002