“The language of Merz now finds acceptance, and today there is scarcely an artist working with materials other than paint who does not refer to Schwitters in some way.”

—Gwendolen Webster

“I could see no reason why used tram tickets, bits of driftwood, buttons, and old junk from attics and rubbish heaps should not serve well as materials for paintings; they suited the purpose just as well as factory-made paints.”

—Kurt Schwitters

Last November I had the good fortune to find myself close enough to Berkeley, California to attend Kurt Schwitters: Color and Collage, the first U.S. museum exhibition in 25 years to focus exclusively on his towering work. I was able to spend as much time as I wanted (at the Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive), studying about 80 examples of his collage and assemblage. It was an experience that is almost impossible for me to describe. I suppose that I should at least try.

KS has been a powerful influence on my personal artistic journey, for good or ill. When I first learned of this exhibition, it seemed beyond my Kentucky reach, but circumstances conspired to place me in the Bay Area on the day after Thanksgiving. During the trip west, I began to greatly anticipate what I knew would constitute more than a singular research event for me. It felt like a pilgrimage, or a potential culmination of sorts, that might “release” me in some meaningful way. My notion could not have been more off target. Hours of arms-length appreciation and up-close inspection served only to solidify my bond with the German innovator. Seeing masterpiece after masterpiece would crystallize a deep awareness that one need not ever shy away from drawing water from the well of this man’s insights, any more than a musician might hold at a distance Wagner, Stravinsky, or Ellington. Should I be concerned a critic may judge my works as derivative of his? Should a mathematician fear being described as an imitator of Einstein? Should a naturalist worry that others might say, “He thinks too much like Darwin”?

The works were superbly organized in a space that allowed for the full range of observation. The guiding concept of the exhibition was the idea that the artist always considered himself a painter. As Clare Elliott writes, “His practices of painting and collage were so intertwined that it is often difficult to determine if paint was applied to paper before or after it was pasted onto the surface, or mixed into the paste itself.” I doubt if KS, a trained painter, made any distinction. We must remind ourselves that there was no clear sense of collage as a separate medium, in the way we understand it today. It was more about his drive to radically expand the choices involved in how one creates a painting to include any material from the surrounding environment of mundane existence.

The rooms were dotted with descriptive panels that presented some of the most incisive remarks I had ever read about Schwitters. Sadly, the catalog edited by Isabel Schulz had already sold out. (Now available for $200 from Amazon, it was being offered for $40 when the show opened.) On top of it all, I did an inordinate amount of note taking and dared to strike up conversations with strangers viewing the show— something I recall never having done before at a museum. Needless to say at this point, it was a pinnacle experience for me. I finally understood that to entertain the hope of moving beyond an artistic influence of this magnitude, I needed to internalize it as fully as possible to discover my own points of departure. I needed to understand how Merz was fundamentally different than Dada, how KS became a revolutionary without being a rejectionist, and how strongly he must have believed in his initiating a spirit of unification that would encompass artistic methods and approaches not even “invented” yet.

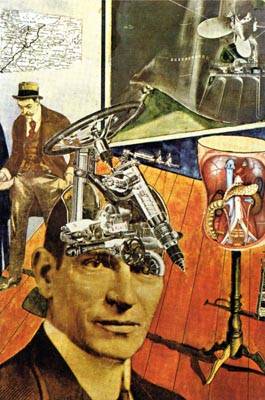

Mz 601

collage by Kurt Schwitters, 1923

paint and paper on cardboard

15 x 17 inches, Sprengel Museum, Hanover