Archive for the ‘K Schwitters’ Category

Saturday, December 8th, 2012

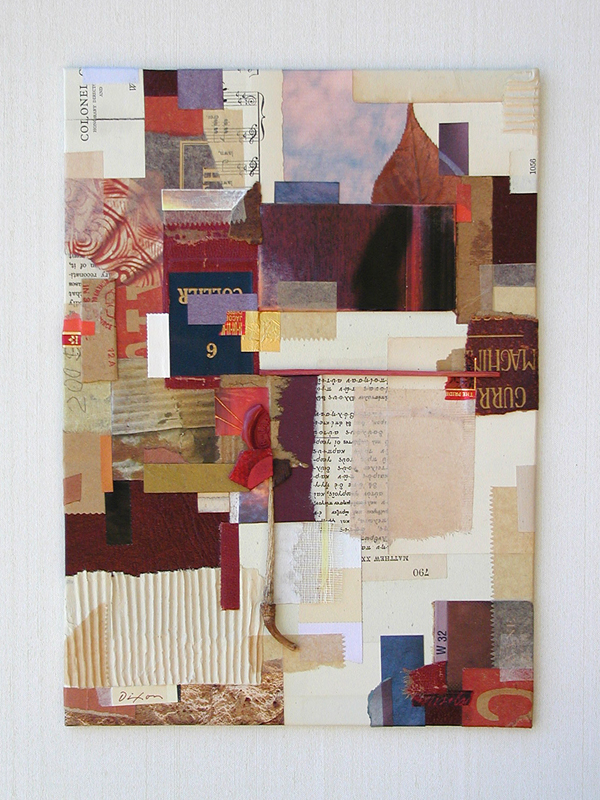

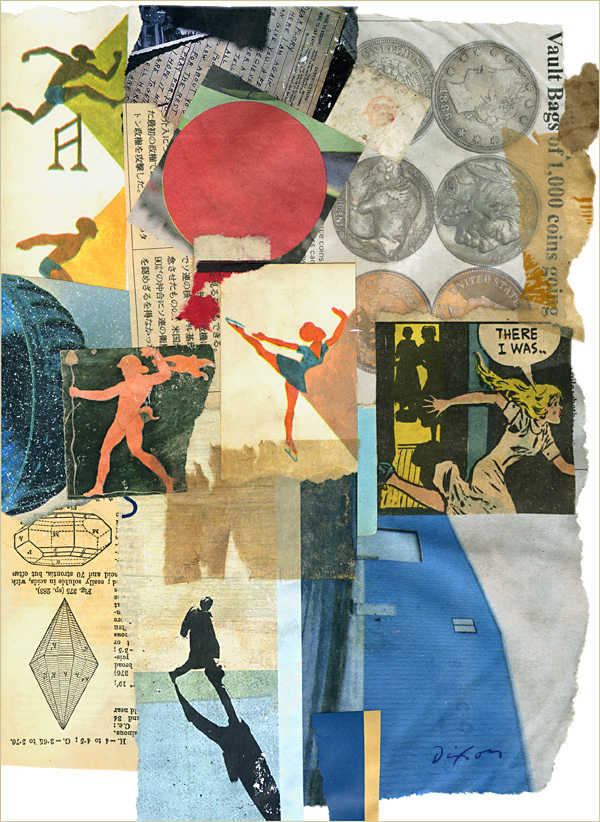

“He spread flour and water over the paper, then moved and shuffled and manipulated his scraps of paper around in the paste…. Finally, he removed the excess paste with a damp rag, leaving some like an overglaze in places where he wanted to veil or mute a part of the color.”

— Charlotte Weidler

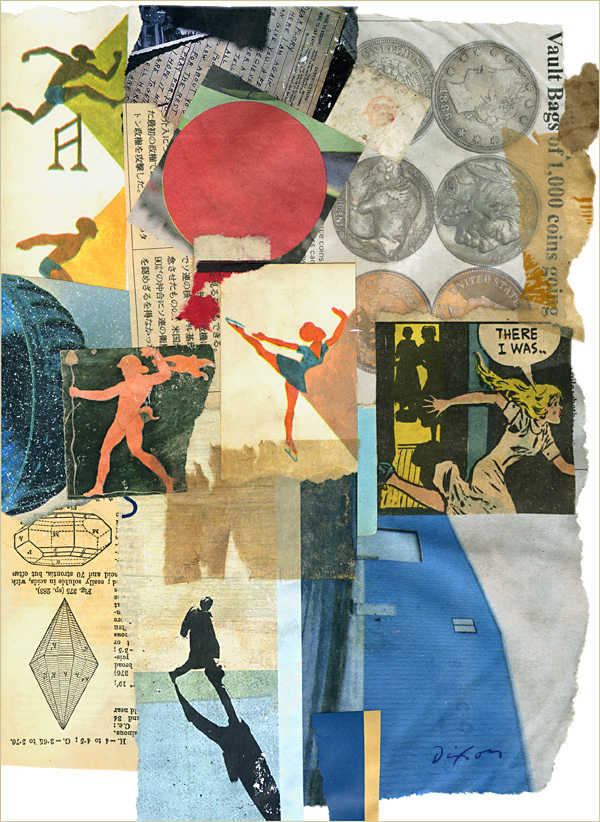

It has been more than a year since I had the humbling opportunity to study dozens of Kurt Schwitters originals at the Berkeley Art Museum. I read the description by the art historian Charlotte Weidler that same day, but I only recently decided to experiment with the paste method she observed. I have always worked with a variety of adhesives, and I often combine more than one in a single collage, never hesitating to literally mix them together (white glue + acrylic varnish, for example). I was impressed with how good some of Kurt’s compositions had held together after 70 to 80 years. I dug out a small package of paper-hanger’s wheat paste acquired in the 1970s, with the new intention of using it to produce a collage on canvas that would stand on its own as an object when finished. Although I expected to coat the final surface later with gel medium, for my first piece based on using the same adhesive as the pioneering artist, I was mainly interested in how wheat paste would affect my process.

The artwork is undone, but I share one of my separate experiments below. I could not be more pleased with the results of this approach. The paste dries slowly. This allows for repositioning, easy removal of excess, and it cures to a flat, velvety finish. I am especially pleased with how conducive it is to manipulating coated paper torn from magazines, an ingredient I am quite fond of. I lightly sand the reverse side, adding a bit of white glue to the paste for good measure, and, using this hand-pasting technique, I have never found “mag scrap” more easy to work with. It may not seem like a big deal to those who attend diverse workshops and demonstrations, but, as a self-taught collage artist, it feels like a significant breakthrough to me.

Now, the only question that remains is one of durability. The seminal works of K.S. show every sign of lasting a century in decent shape, but I am no museum expert, nor have I been as fixated on archival longevity as some collage artists I know. I expect my creations to age, perhaps in unexpected ways. This reminds me of an online discussion not long ago about using elements taken from newspapers. Many collage artists may share my expectation that a newsprint ingredient will simply mature as nature sees fit, adding a certain “wabi-sabi” aspect to a work of art that relies on found material. Who knows what Picasso or Braque thought about the nature of impermanence when each created their first collage with that famous wood-grain paper found in a store? Or, for that matter, what Schwitters himself thought when— with seemingly little regard for acid-free niceties —he built the enduring concepts of Merz on the detritus of ordinary life?

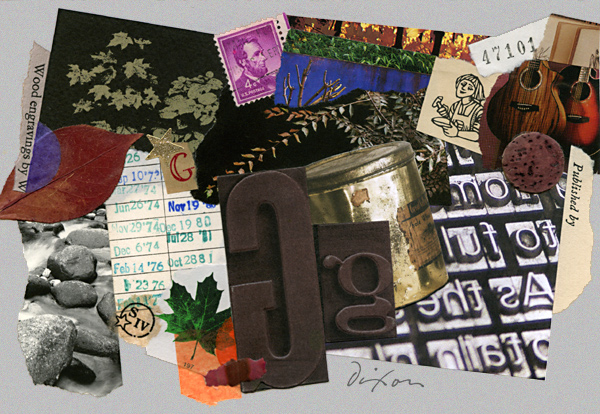

There I Was

collage experiment by J A Dixon

8.75 x 11.5 inches, not for sale

Posted in Collage, Demonstrations, Exhibitions, Experiments, G Braque, Influences, Ingredients, J A Dixon, K Schwitters, Merz, Methodology, P Picasso, Technique | No Comments »

Saturday, October 27th, 2012

“I value sense and nonsense alike. I favor nonsense, but that is a personal matter.”

— Kurt Schwitters

When creating a collage, there is no right or wrong approach, but I can’t help but notice the extent to which some artists go in their obvious effort to be clever. Whether one seeks the visual pun, an intellectual twist, or utter shock value, I think all of us would hope to avoid a result that looks too “gimmicky.” For many of us, the goal is to find a desirable place on a spectrum that extends from the fully honed concept to the purely unconscious response. There are times when the progression from start to finish is a smooth, natural flow. More often than not, the process becomes a balancing act of decisions. The artist weighs the various relationships between layers of overt connotation and covert significance. Blending levels of stark clarity with obscurity, insinuation, and nuance is what gives the medium of collage its distinctive power.

The artist weighs the various relationships between layers of overt connotation and covert significance. Blending levels of stark clarity with obscurity, insinuation, and nuance is what gives the medium of collage its distinctive power.

In The Essential Joseph Cornell, Ingrid Schaffner delineates the various threads of underlying meaning in Cornell’s “A Pantry Ballet (for Jacques Offenbach),” and how the artist weaves together French Romantic poetry, Lewis Carroll, lobsters, metaphysics, and the once-scandalous cancan. She explains how his work “was built on the power of association and was so well constructed that it is less essential for us to understand all the references than it is to let our mind wander and play with the images.” There is perhaps no artist who influenced the middle decades of the hundred-year history of collage more than Cornell. His constructions demonstrate just how seamless the balance of conscious and subliminal meaning can become in a work of art.

I like to produce compositions without the motive force of intention, but I also enjoy working with an organizing idea or theme. During the course of its creation, a collage may rely on either principle. A piece might begin as sheer abstraction and evolve toward symbolic implications. On the other hand, it might begin with a mental construct that invites other types of intuition and gut reactions. The essence of collage is complex, synergistic, alchemical. Let us all make more!

Cyclic Attraction

collage miniature by J A Dixon

7.75 x 3.375 inches

collection of G Zeitz

Posted in Assemblage, Collage, Influences, J A Dixon, J Cornell, K Schwitters, Methodology, Symbolism | No Comments »

Monday, October 22nd, 2012

“I could see no reason why used tram tickets, bits of driftwood, buttons, and old junk from attics and rubbish heaps should not serve well as materials for paintings; they suited the purpose just as well as factory-made paints.”

— Kurt Schwitters

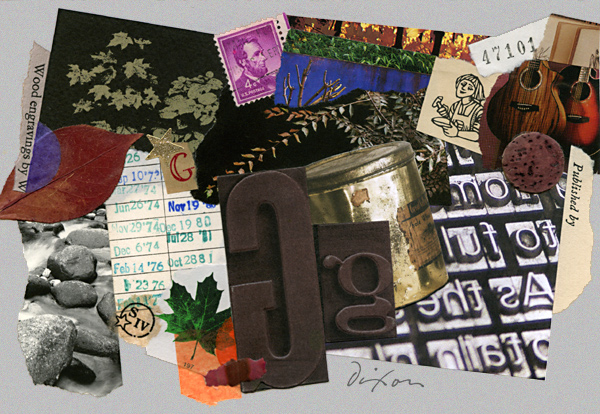

There may be no more delightful aspect of collage than the realization that this medium can be pursued endlessly without the need for costly materials. The only significant budgetary item is creative time. True, we all want to document our work and frame it handsomely, but that same desire is an across-the-board constant for all fine artists. The activity itself is within the reach of everyone, regardless of economic means. Anyone can create value from substance that has virtually no intrinsic worth. An artist who uses nothing more than a pencil still wants to draw on a lovely, well-made piece of paper. By contrast, the working surface for a collage can derive from the same cast-off resources as the ingredient found material. How wonderful a world is that?

Disney Sauce

collage miniature by J A Dixon

3 x 3 inches, not for sale

Posted in Collage, Ingredients, J A Dixon, K Schwitters, Technique | No Comments »

Saturday, September 29th, 2012

“To say that Kurt Schwitters was an amazingly versatile artist and anticipated much is such an absurd understatement that the remark is almost Dada.”

—Walter Hopps

“And so you will understand why we have had enough of Dada. The mirror that indignantly rejects your worthy countenance, that in mirroring it banishes it, such a mirror does not love you, it is in love with the very opposite.”

—Kurt Schwitters

To perpetually imitate KS is to be as unlike him as one could conceive. He was always pushing forward into the untried. But it is not for every artist to cross a boundary into the unknown. Some of us might be better suited to settling the frontier. There may be some among us more appropriately equipped to continue investigating the discoveries of a pioneering original— by sharing these visual concepts with a broader audience, by weaving them into a greater tapestry of the visual landscape, and, with a bit of luck, by finding a way to fuse our unique perspective with what has been handed off to us, in order to express new ideas that further cultivate a valuation of the past.

I am not an expert on Dada or the relationship of Schwitters with the phenomenon. I am always learning more. I just know that he was never fully accepted by the movement at its peak, and that he was compelled to articulate his own vision of Merz. Perhaps much of it relates to Fascist oppression and the resulting geographic disruption, but I’ve always believed there was more to it than that. More important to me is an ongoing effort to unravel the underlying differences. A certain veneration for painting, design, and the aesthetics of beauty probably set KS apart from some of his rejectionist or surrealist contemporaries, but that is what gives his creations a unique, seminal power for me and for others. His perseverance in the face of daunting circumstances and a professed goal of “creating relationships, preferably between all things in the world” fly in the face of a nihilist orientation. Although I remain awed by surrealism in collage, and I am as tickled by irreverent juxtapositions as the next guy, there is an inherent pessimism or metaphysical anarchy in the “art of weirdness” that never seems to resonate with my deepest creative urge. I cannot say that I fully understand that, or that I am not occasionally moved to place a fish head on a reclining nude or mask a face with a front-loading washer. Is it even productive for me to engage in such self-analysis? Or, is it important only to submit to the most undeniable inner motivations when in the studio, sorting through another pile of visual fragments that await an intuitive response?

Unconditional Surrender

collage artifact by J A Dixon

collection of Nancy and Charles Martindale

Posted in Artifacts, Collage, Dada, Influences, J A Dixon, K Schwitters, Merz, Surrealism | No Comments »

Sunday, September 23rd, 2012

“The language of Merz now finds acceptance, and today there is scarcely an artist working with materials other than paint who does not refer to Schwitters in some way.”

—Gwendolen Webster

“I could see no reason why used tram tickets, bits of driftwood, buttons, and old junk from attics and rubbish heaps should not serve well as materials for paintings; they suited the purpose just as well as factory-made paints.”

—Kurt Schwitters

Last November I had the good fortune to find myself close enough to Berkeley, California to attend Kurt Schwitters: Color and Collage, the first U.S. museum exhibition in 25 years to focus exclusively on his towering work. I was able to spend as much time as I wanted (at the Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive), studying about 80 examples of his collage and assemblage. It was an experience that is almost impossible for me to describe. I suppose that I should at least try.

KS has been a powerful influence on my personal artistic journey, for good or ill. When I first learned of this exhibition, it seemed beyond my Kentucky reach, but circumstances conspired to place me in the Bay Area on the day after Thanksgiving. During the trip west, I began to greatly anticipate what I knew would constitute more than a singular research event for me. It felt like a pilgrimage, or a potential culmination of sorts, that might “release” me in some meaningful way. My notion could not have been more off target. Hours of arms-length appreciation and up-close inspection served only to solidify my bond with the German innovator. Seeing masterpiece after masterpiece would crystallize a deep awareness that one need not ever shy away from drawing water from the well of this man’s insights, any more than a musician might hold at a distance Wagner, Stravinsky, or Ellington. Should I be concerned a critic may judge my works as derivative of his? Should a mathematician fear being described as an imitator of Einstein? Should a naturalist worry that others might say, “He thinks too much like Darwin”?

The works were superbly organized in a space that allowed for the full range of observation. The guiding concept of the exhibition was the idea that the artist always considered himself a painter. As Clare Elliott writes, “His practices of painting and collage were so intertwined that it is often difficult to determine if paint was applied to paper before or after it was pasted onto the surface, or mixed into the paste itself.” I doubt if KS, a trained painter, made any distinction. We must remind ourselves that there was no clear sense of collage as a separate medium, in the way we understand it today. It was more about his drive to radically expand the choices involved in how one creates a painting to include any material from the surrounding environment of mundane existence.

The rooms were dotted with descriptive panels that presented some of the most incisive remarks I had ever read about Schwitters. Sadly, the catalog edited by Isabel Schulz had already sold out. (Now available for $200 from Amazon, it was being offered for $40 when the show opened.) On top of it all, I did an inordinate amount of note taking and dared to strike up conversations with strangers viewing the show— something I recall never having done before at a museum. Needless to say at this point, it was a pinnacle experience for me. I finally understood that to entertain the hope of moving beyond an artistic influence of this magnitude, I needed to internalize it as fully as possible to discover my own points of departure. I needed to understand how Merz was fundamentally different than Dada, how KS became a revolutionary without being a rejectionist, and how strongly he must have believed in his initiating a spirit of unification that would encompass artistic methods and approaches not even “invented” yet.

Mz 601

collage by Kurt Schwitters, 1923

paint and paper on cardboard

15 x 17 inches, Sprengel Museum, Hanover

Posted in Assemblage, Collage, D Ellington, Dada, Exhibitions, Influences, Ingredients, J A Dixon, K Schwitters, Methodology, Music | No Comments »

Monday, September 17th, 2012

“When we look at (the work of) Schwitters, we must realize that it was made in a time with its own historical zeitgeist. The attitudes of the time, the philosophies, the hopes and the fears are impossible to duplicate today. We live in a different age, with three times the population, with technologies they could only dream about. So if one finds inspiration … it must manifest itself in the present. This has deep implications. The radical-ness, the surprise and sense of discovery, and the freshness that Schwitters was able to experience through his process is now a known part of history.”

—George Rodart

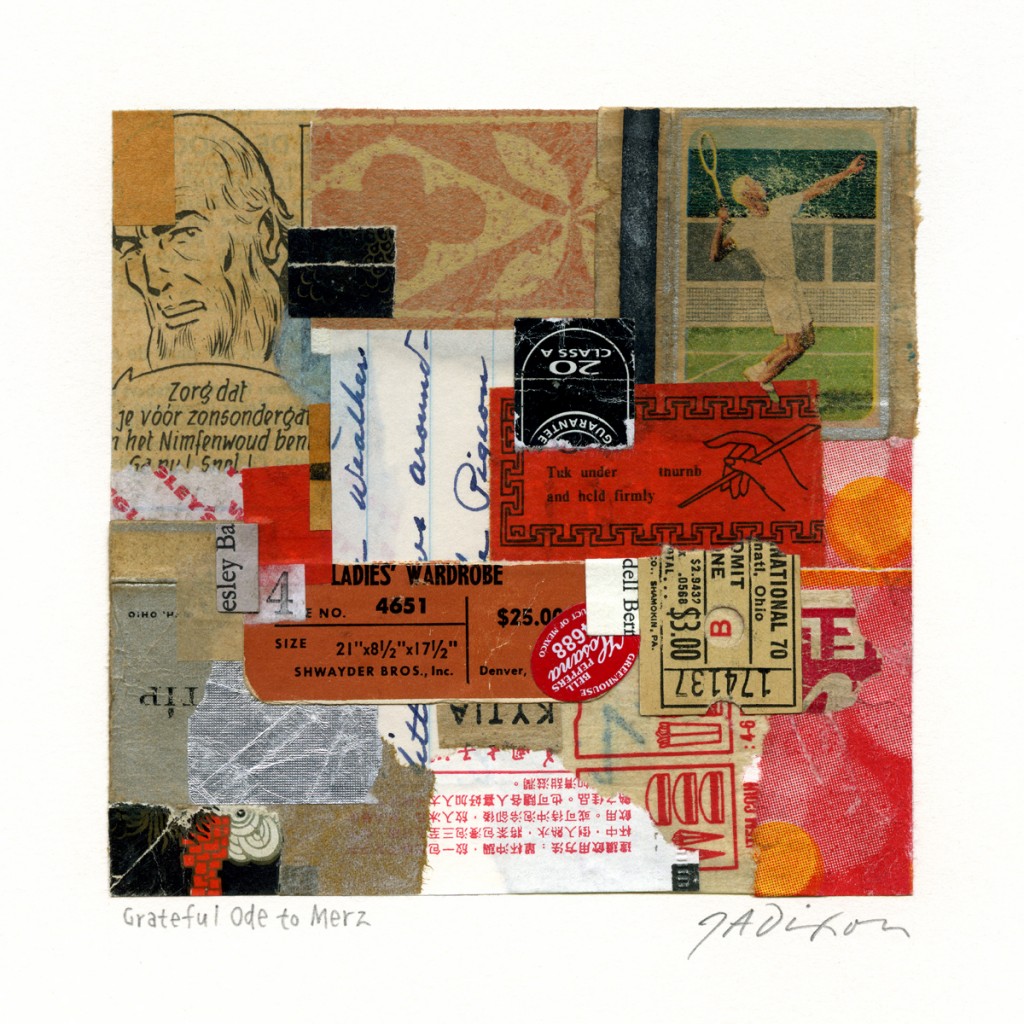

Four of my works have been acquired by the Ontological Museum in connection with the centennial of collage, 1912–2012. Collage artists worldwide owe a debt of gratitude to Cecil Touchon for his extraordinary labor on behalf of the medium. Working for years to establish this important institution, his efforts leading up to and during 2012 will be long considered one of the most significant developments (if not the most significant) during this milestone year. The centennial exhibition in Pagosa Springs opened last week. It features more than 400 works contributed to the museum’s permanent collection from artists living in 30+ countries and will be on view through May, 2013. This exceptional exhibition can be viewed online in its entirety.

No visual art form is more vital than collage on its one-hundredth birthday. Certainly there are antecedents in mosaic, the fabric arts, and various folk traditions, but historians have decided that either a Frenchman or a Spaniard first crossed a significant threshold a dozen years into the previous century. Some may continue to debate whether collage as a technique was “invented” by Georges Braque or Pablo Picasso, but in my considered view, the seminal genius of the medium was Kurt Schwitters, perhaps the first modern artist to fully master the process. I’m not alone in this opinion, and my conviction should be no surprise to anyone who has discovered this blog.

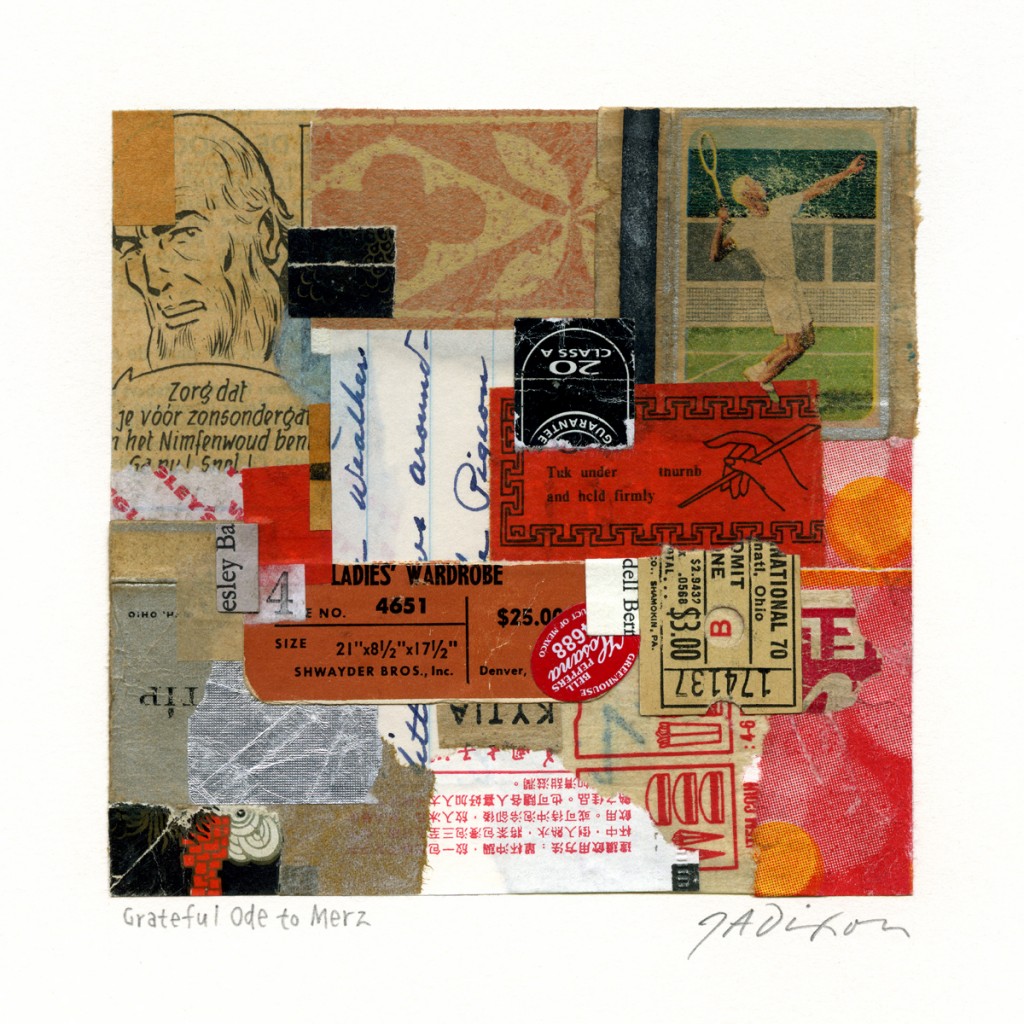

Grateful Ode to Merz

collage miniature on Bristol by J A Dixon

homage to Kurt Schwitters

collection of The Ontological Museum

Posted in C Touchon, Collage, G Braque, J A Dixon, K Schwitters, P Picasso | No Comments »

Friday, September 7th, 2012

“Though he was not connected with any political party, his art was regularly vilified as a threat to traditional German values, while he himself was denounced as ‘unpatriotic’ or, just as often, insane. Yet Schwitters thrived on public opposition, and from 1919 to 1923 he created a succession of Merz pictures which are now seen as his greatest contribution to twentieth century art. These pictures carry an inner tension that derives from the sensitive juxtaposition of abstraction and realism, aesthetics and rubbish, art and life, and their innate dynamism is one of the characteristics of Merz.”

— Gwendolen Webster

Today’s featured collage, inspired by some of the superlative work being done by my friends during this centennial year for the medium, is a bit larger than my typical miniature. To produce an “artifact,” I began with the cover of a ruined book, and before long I realized I had a strictly nonrepresentational composition on my hands. Created spontaneously at a close viewing distance, it wasn’t until I stepped back after completion that it brought to mind the kind of image one might view from the window of an upper story, looking across an urban landscape, with light and shadow playing off facades and roof lines. The way in which the mind attempts to unravel layers of symbolic meaning from the purely abstract is endlessly intriguing to me.

Those of us who create art within this particular genre are indebted to the increasingly exalted legacy of Kurt Schwitters and his original conception of Merz. I often think about how we have been liberated to explore the inexhaustible potential of this approach and to disclose our aesthetic vision within the accepted playground of modern art. Never forget that the man who fully defined this visual language for us did so at genuine risk to his personal freedom and safety. We may not always describe our works as a tribute to the enduring idea of Merz, but that is precisely what they are. Schwitters said, “Merz means creating relationships, preferably between all things in the world.” One fine aspect of that is the new connections and friendships that grow out of mutual interest in collage during its one-hundredth year. Check out the online galleries of Launa D Romoff, Teri Dryden, Scott Gordon, and Joan Schulze. You may agree with me that these artists are among today’s “Heirs to KS.” I hope to discover many more and to share their creative output at this site. Please stop by again soon.

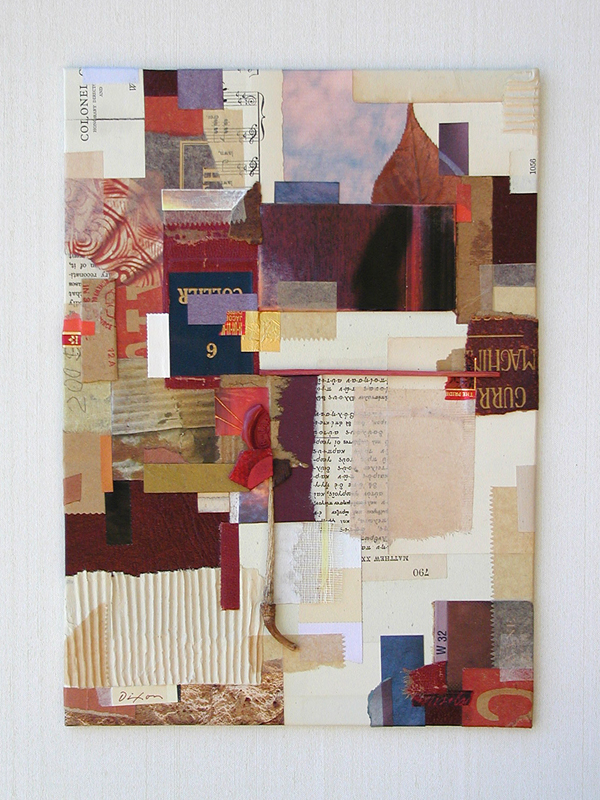

Structural Integrity

collage artifact by J A Dixon

8 x 10.5 inches

• S O L D

Posted in Abstraction, Artifacts, Collage, Influences, J A Dixon, J Schulze, K Schwitters, L Romoff, Links, Merz, S Gordon, T Dryden | 4 Comments »

Saturday, August 25th, 2012

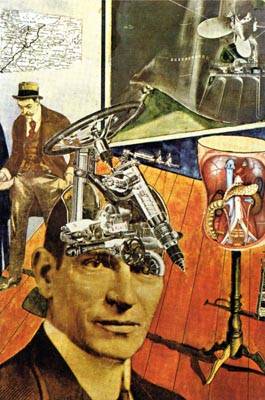

I’m keen on art history to quench a dry spell. Here’s my suggestion to a collage artist in a slump.

• Browse modern art movements that have influenced collage: cubism, dada, constructivism, expressionism, surrealism, pop art.

• Relax and study the seminal masters of the medium: Cornell, Paolozzi, Höch, Hausmann, Schwitters.

• Then go to your “morgue” of images, textures, ephemera, and found material: group various ingredients into piles, responding quickly, intuitively, and without conscious thought for composition or symbolic associations.

• Before you know it, you’ll have more ideas and embryonic projects than you can immediately deal with. React first to the ones that won’t be denied. With a bit of luck, a new series will emerge.

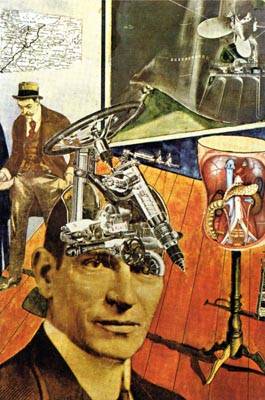

Tatlin at Home

by Raoul Hausmann

1920

Posted in Constructivism, Cubism, Dada, E Paolozzi, Expressionism, H Höch, Influences, Ingredients, J Cornell, K Schwitters, Methodology, Pop Art, R Hausmann, Surrealism | No Comments »

Wednesday, August 22nd, 2012

“Ray didn’t talk about it, he just did it. That’s why you don’t find art magazines lying around quoting the art philosophy of Ray Johnson.”

—Toby Spiselman

Ray Johnson, the original “most famous unknown artist in the world,” produced his A Book About Death during the years 1963 to 1965. The pages were randomly mailed and offered for sale. Complete copies were compiled by a rare few. Johnson was a significant bridge between the groundbreaking work of Schwitters, the sensibilities of Cornell, and the emergence of what would become the most widely recognizable features of Pop Art. He was highly influential in the Mail Art, Installation Art, and Performance Art movements, as well as late 20th-century neo-Dadaist trends. Paris-based Matthew Rose has actively aroused a worldwide interest and vitality that perpetuates the legacy of A Book About Death, including a 2010 incarnation (in which I made a small contribution). The full history can be studied at this site.

ABAD 2010

collage miniature by J A Dixon

6 x 4 inches, not for sale

Posted in Collage, Dada, Exhibitions, Influences, J A Dixon, J Cornell, K Schwitters, Links, M Rose, Pop Art, R Johnson | No Comments »

Friday, August 3rd, 2012

“A ship in harbor is safe, but that is not what ships are built for.”

—John Shedd

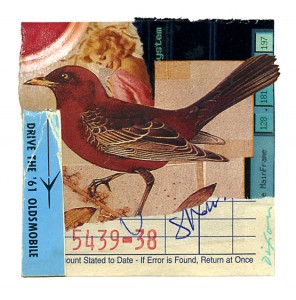

For some time now I’ve been observing how Matthew Rose and Randel Plowman make effective use of birds, and I acknowledge that there is something irresistible about including them in a collage. Most likely, it goes back to Joseph Cornell’s aviaries. I also noticed that I placed a bird in my Face with Asparagus as a sort of eyebrow. I intend to use that image as the “face” of The Collage Miniaturist. Below is a study lifted from one of my personal journals, which tend to be caught between a collection of organizational lists, private anecdotes, and diary of thumbnail sketches.

Since I’ve posted my review of Kathleen O’Brien’s recent exhibition, it’s probably time to sail this boat out into open water. Thinking of birds, perhaps I should say instead, fly out of the nest, —or— drive that ’61 Oldsmobile to a destination unknown. Tomorrow sounds good.

The ’61 Olds

collage miniature by J A Dixon

3 x 3 inches, not for sale

Posted in Collage, Influences, J A Dixon, J Cornell, K O’Brien, K Schwitters, M Rose, R Plowman, Thumbnails | No Comments »

Wednesday, August 1st, 2012

“Books are to be called for and supplied on the assumption that the process of reading is not a half-sleep; but in the highest sense an exercise, a gymnastic struggle; that the reader is to do something for himself.”

—Walt Whitman

When I hear artists say they try to limit their influences, I think, “Nonsense.” Outside of some strange brand of sensory or cultural deprivation, it is simply not possible to avoid influences. That being said, why not regularly go to the masterworks and primary sources for direct, conscious influence to balance or offset the continuous bombardment of visual input from a culture steeped in nth-generation bastardizations? One cannot drive down a street, walk through a shop, or scan the media without being influenced in some way by a legion of art directors, graphic designers, and photographers—and these individuals may or may not have any direct knowledge of how they are re-cycling the ideas of innovative artists. Great writers understand where the basic narrative modes originated. Serious filmmakers know who first did this or that—a dream montage, in-camera trick, or other cinematic effect. One cannot imagine a Morricone who did not know a Beethoven who had never listened to Bach or Haydn. There is no way to conjure up an Emerson who did not know a Montaigne who had never read Lucretius or Diogenes.

The point of this is not to find fault, but to serve as a lead-in for what I intend to be a series of posts about my take on the primary innovators within the evolving medium of collage. Credit must be given to Braque, Picasso, Gris, Duchamp, and others, but, for me, the study must begin with Kurt Schwitters and Joseph Cornell. Any person dedicated to collage who neglects these masters will fail to understand the foundation of the art form. What student hasn’t thrilled to her first startling, Höch-like montage, cut and assembled from discarded magazines? What young person does not, at some point in his creative formation, place a few found objects in a small box, pause to consider the intriguing effect, and not wonder, “Is it art?” Ultimately, what I end up saying here about the key historical figures is far less important than the overwhelming need for you to put your ideas and feelings into context with each one’s remarkable body of work, according to your own perceptions and priorities. For those who encounter their creations for the first time, the inevitable thought will be, “So, he was the first guy to do that…” (except in the case of Höch, of course). Whether one rejects, reveres, ignores, imitates, or “rips off” the great seminal works of collage, one must do so with full awareness. Walt Whitman’s admonishment to writers can equally apply to visual artists. Except for those who approach the medium of collage as a hobbyist, we owe it to ourselves to partake of the “gymnastic struggle.”

Gris | Schwitters | Höch | Cornell

Posted in Artists/Collage, Collage, G Braque, H Höch, Influences, J Cornell, J Gris, K Schwitters, P Picasso | No Comments »

The artist weighs the various relationships between layers of overt connotation and covert significance. Blending levels of stark clarity with obscurity, insinuation, and nuance is what gives the medium of collage its distinctive power.

The artist weighs the various relationships between layers of overt connotation and covert significance. Blending levels of stark clarity with obscurity, insinuation, and nuance is what gives the medium of collage its distinctive power.