On Kurt Schwitters

“The mission of the museum is to create a collection that is gathered together like a scientific museum that collects rocks or bugs or perhaps like an anthropological museum. It is an art project using the idea of the ‘museum’ as a new art genre. It is a cultural record of contemporary art that is unique, in that it is not based on preciousness or on the collections of wealthy collectors like most art museums are. It is an artist-oriented research museum developed around living connections to artists all over the world primarily through the internet. The works that come into the collection are normally donated by the artists as independent gifts or in response to a particular project or exhibition. The collection contains thousands of items with more added continuously.”

— Cecil Touchon

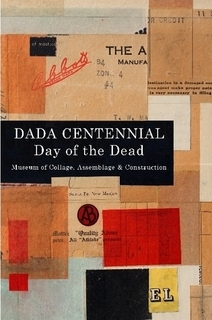

The Collage Miniaturist sincerely thanks Cecil Touchon for including my essay in the ‘Dada Centennial / Day of the Dead’ exhibition catalog, but, most of all, for volunteering so much of his time to this historic observation and to the ongoing administration of the institution he founded, now located in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Please purchase the publication as a valuable collector’s item. The full text of my essay is published below:

On Kurt Schwitters and a Century of Dada

by John Andrew Dixon

I could see no reason why used tram tickets, bits of driftwood, buttons, and old junk from attics and rubbish heaps should not serve well as materials for paintings; they suited the purpose just as well as factory-made paints.

― Kurt Schwitters

Though he was not connected with any political party, his art was regularly vilified as a threat to traditional German values, while he himself was denounced as ‘unpatriotic’ or, just as often, insane. Yet Schwitters thrived on public opposition, and from 1919 to 1923 he created a succession of Merz pictures which are now seen as his greatest contribution to 20th-century art.

― Gwendolen Webster

After a century, the gongs of Dada still reverberate, and the movement’s impact on art continues. As a creative perspective, it retains a robust stature among contemporary collage artists. Even a cursory review of recent collage output exposes an enduring influence, weaving its way through the work of students, emerging professionals, veteran practitioners, and current masters of the medium. What began as a revolt against visual traditions has ironically become an inseparable part of our aesthetic heritage.

As a collage artist, I find the medium’s beginnings endlessly fascinating. Although credit for originating collage is customarily granted to the Cubists ― art historians can debate whether the technique was “invented” by Georges Braque or Pablo Picasso ― no group shaped its emergence more powerfully than the early 20th-century Dadaists and their successors, the Surrealists. Despite the short apex of their schools of thought, few approaches in contemporary collage have arrived in 2016 without navigating the tributaries they established. During this centennial year, much will be said and written about the catalytic Hugo Ball and the seismic effect that occurred after his opening Zurich’s Cabaret Voltaire with Emmy Hennings in February, 1916. Most of the work being created under the banner of collage has not escaped the hundred-year shadow of sensibilities unleashed on modern art by those who first uttered “Dada!” ― spontaneity, chance, illogic, irreverence, consternation, and, perhaps foremost, a rejectionist posture. Most collage artists of our time would disagree with Ball’s exhortation to “burn all libraries and allow to remain only that which everyone knows by heart.” However, they may relate to his conclusion that “this humiliating age has not succeeded in winning our respect.”

Warsaw-based designer/educator and blogger Annę Kłos describes Dada as a “world view.” Yet, she reminds us that, by its very nature, it could not be homogeneous, and that the groundbreaking Merz Pictures of Kurt Schwitters were produced before a backdrop of internal incompatibilities. Artists have a tendency to lump the Dadaists together and emulate their visual and intellectual departures as an encompassing genre, a mere style, or, at worst, a bag of tricks. Few are able to put the photomontages of Hannah Höch or Raoul Hausmann into historical context and trace Dada’s inherent, but elusive, characteristics and how they penetrated decades of innovation, including the originality of Cornell, Rauschenberg, Nevelson, Johnson, Schneemann, Ruscha, Maciunas, Hamilton, or Kolář. Being no scholar, I would not attempt to do so here. My purpose is to emphasize the need for more awareness of the towering influences that have shaped our approach to collage and assemblage. As we build on the legacy of Dada — having left behind the musty trappings of Weimar Republic protest, Trotskyite dilettantism, and an overt hostility toward religion — the challenge for contemporary, “post-centennial” collage artists is to push beyond vintage expressions and to explore ideas that begin with the material cast off by today’s diverse, but enormously wasteful, culture.

When Kurt Schwitters was asked, “What is art?” he replied, “What isn’t?” He saw no boundaries and pushed forward into areas untried. To imitate Schwitters is to be unlike him, but can it be the scheme of every artist to plunge into the unknown? Are some of us more suited to settling the frontier instead? We may be better equipped to investigate the discoveries of a pioneering original, to share these visual concepts with a broader audience, and to weave them into the greater tapestry of our visual landscape. With a bit of luck, we may find a way to fuse our unique creative aspects with what has been bequeathed to us, expressing visual ideas relevant to our own time and sense of place while cultivating an enhanced perception and valuation of the past.

I am gratified to have been asked to share these thoughts, but I am not an expert on Dada or the relationship between Schwitters and the European faction. I continue to learn more about those turbulent times and to understand why many Dada enthusiasts never accepted him as the movement reached its peak. What gives his creations a distinctive seminal power is how they bear veneration for painting, design structure, and the aesthetics of beauty over a borderline previously uncrossed. Robert Hughes describes their compositions as “based on a firm Cubist-Constructivist grid,” and “despite the contrast of materials, their edges, thicknesses, surfaces, and colours are exactly calibrated, and the fragments of lettering serve much the same ends as they did for Braque and Picasso — to introduce points of legible reality into the midst of flux.” These same qualities probably set Schwitters apart from rejectionist contemporaries, many of whom repudiated all precedents and could not abide his indifference to political activism. His professed goal of “creating relationships, preferably between all things in the world” would fly in the face of the era’s extreme skepticism. He was compelled to articulate his own radical vision, and he called it Merz (an appellation derived from an ad for the Kommerz und Privat-Bank that appeared as a typographic scrap in one of his collage artworks).

Walter Hopps observes that “to say Kurt Schwitters was an amazingly versatile artist and anticipated much is such an absurd understatement that the remark is almost Dada.” For me to point out that he persevered in the face of scorn and daunting circumstances also verges on understatement. After fleeing Hitler’s Germany to join his son in Norway, he escaped the Nazi invasion in a fishing boat forced to evade torpedo attacks. After a period of internment, he resettled in the lake district of England and died at age 60 in 1948, before the careening world of art had paused to digest and appreciate his obscure masterworks. His legendary Merzbau was destroyed when the Allies bombed Hanover, and what was left of his attempt to recreate it in exile was later razed. At his death, he was working on his third version, a strange “shrine” in a countryside barn. Although it survives as one of the unparalleled fabrications of the mid-century, his lasting contribution to modern art is the integrative spirit of Merz.

Inherent within bizarre-for-its-own-sake art is a kind of pessimism or metaphysical anarchy that is absent in the creative breakthroughs of Schwitters. His works foreshadow Popism, as well as installation and performance art. Gwendolen Webster observes that “The language of Merz now finds acceptance, and today there is scarcely an artist working with materials other than paint who does not refer to Schwitters in some way.”

As Clare Elliott writes, “His practices of painting and collage were so intertwined that it is often difficult to determine if paint was applied to paper before or after it was pasted onto the surface, or mixed into the paste itself.” I doubt if Schwitters, an experienced painter, made any distinction. We must remind ourselves that there was no clear sense of collage as a separate medium in the way we understand it today. It was more about his drive to radically expand the choices involved in how one created art and to include any mundane material from the surrounding environment. Of course, the medium had other early pioneers, but it is difficult to imagine the trajectory that collage might have taken without his sweeping influence. As a collage artist, I shall continue to examine how Merz was intrinsically Dada (yet different), to perceive how Schwitters was a revolutionary without becoming a rejectionist, and to hold in high regard his belief in a spirit of unity that encompassed undiscovered artistic pursuits.

It is not an easy thing to defy expectations, one’s own or anticipated responses, but a collage artist must respect and acknowledge the past with a clear mind, internalize it as a part of the intuitive process, and follow a personal investigation anchored on risk. It is natural for an artist to seek and refine an individual voice, but one need not shy away from tapping an innovator’s insights, any more than a composer might hold at a distance Stravinsky, Ellington, or Cage. Should we be concerned that a critic may judge our works as derivative? Should a mathematician fear being described as an emulator of Einstein? Should a naturalist worry that others might say, “She thinks too much like Darwin”? Personally, I have no qualms about continuing to respectfully mine the rich vein of creative ore that Schwitters exposed. Whether it proves to be a nonrenewable resource has yet to be shown.

As Dada celebrates its one-hundredth birthday, no visual art is more vital than collage. With antecedents in mosaic, the fabric arts, and various folk traditions, collage had no identity or foothold in the new 20th Century. Four years after a Frenchman or a Spaniard first crossed a significant threshold by adhering wood-grain paper to a painting, an unprecedented force erupted in a Swiss nightclub to transform the embryonic form. From that spirit, an artist from Germany would become the first modernist to fully master the process and to serve as the seminal genius of the medium. Those of us who create collage art may not always describe our works as a tribute to the enduring, inclusive concepts of Merz, but that is precisely what they are, and we are indebted to that legacy. Kurt Schwitters, the man who defined this expansive attitude and visual grammar for those who would follow, did so at true risk to his freedom and personal safety. Nevertheless, he was no demigod. Perhaps he was an artist who just wanted to survive and fulfill a visionary urge. Our finest tribute to his Merz may be the new connections and friendships that emerge from a growing interest in the medium and the mutual support necessary to create, exhibit, and preserve the artwork that will mark our contribution to the history of collage.

____________

____________

With a 40-year base as an illustrator and award-winning designer, John Andrew Dixon brings a mature focus to his work as a collage artist. He is an active exhibitor and ruminates on all things juxtaposed at his blogsite, The Collage Miniaturist. He works from a combined studio, gallery, and residence in the heart of historic downtown Danville, Kentucky.